Why Burmese are Seeking Blockchain and Encryption Technology in Myanmar

Author: 7k

Email: SevenKthousand@protonmail.com

English Reviewer: Marcus Khoo

Edited by: Fangting

Intro

I met Htway, a tech consultant from Myanmar, during Chiang Mai's ‘pop-up city’ season. Often dressed in a polo shirt tucked into jeans, he reminds me of a young engineering student. He would flit between book clubs, workshops, and Demo Days, raise his hand in Q&A sessions and say, "I'm from Myanmar. Because of the civil war, many of my people are facing tough circumstances. I wonder if these technologies can help..." The room started to grow somber.

Since the 2021 military coup, aside from reporting centering the conflicts of Myanmar's Civil War or scam centers, general news about the day to day lives of Burmese have been scarce. It drove me to really get to know Htway. One day, after an event, I saw Htway chatting with another Burmese, Kha. Unexpectedly, they were old friends who had lost contact since the coup, and just ran into each other at the event.

Kha is in the crypto industry. In November 2024, Ethereum’s Devcon was held in Bangkok, bringing crypto enthusiasts from around the world to Southeast Asia for the first time. Many, including Vitalik, spent the month before Devcon living and working together in Chiang Mai digital nomad style, in what are knowns as ‘pop-up cities.’ Htway was drawn to these events, despite having no prior experience with cryptocurrencies. He had worked at a startup incubator in Yangon until the coup forced him to leave. Kha, on the other hand, still works within Myanmar, and came to Thailand specifically for Devcon. Due to the military government's illegalization of cryptocurrencies, leaving and entering the country is risky for him. Yet, he tries to travel abroad once a year to ‘stay connected with the outside world’. Like many Burmese, they hope to find practical applications for blockchain and encryption technology in their deteriorating situations.

I had previously written a short piece about Myanmar in Chiang Mai, through which, I got to meet more Burmese who are trying to alleviate the humanitarian crises such as inflation and internet surveillance in Myanmar by technology. They explore possibilities for unmediated international aid and refugee identity verification while facing significant challenges. This inspired me to write another article about Myanmar—one that’s not centered on crime, military, or war (though they are ever-present), but on ordinary people striving to bring change to their home.

The Coup

At 3 a.m. on February 1, 2021, Bradley was awakened by a phone call from a friend: "Look up in the sky!" Confused, he stood by the window, only realizing moments later that this was the code signaling the coup had begun. That day, the Myanmar military announced the overthrow of the country's first civilian government since independence—the National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The military junta was reinstated, and declared a state of emergency. The coup initiated a severe regression from Myanmar’s decade-long opening and developing progress, plunging the country into escalating humanitarian crises and economic decline up to this day.

On the day of the coup, Bradley saw people rushing to buy rice, ATMs not functioning due to internet shutdown, and phones rapidly losing signal. In the following days, protesters faced armed suppression by the military and police. Within weeks, violence escalated against civilians, with journalists in vests becoming direct targets, private homes raided, and by March 22, 2,682 people had been confirmed arrested and 261 killed by the junta. Protesters began to use makeshift weapons, resistance forces in various regions started to fight back, and the civil war began.

Bradley's work focused on internet literacy, including training parliament and government agencies to use the internet. Before February, he had heard rumors of an impending coup. Yet, "no one believed it would happen, not even those in the military," he said. Nevertheless, he and his colleagues devised code words and strategies for communication blackouts. In the first days of the coup, they met in a predetermined park to share information manually: where protests were happening, who had been arrested, whether the military had opened fire. Little did they expect, this kind of struggle would last more than four years.

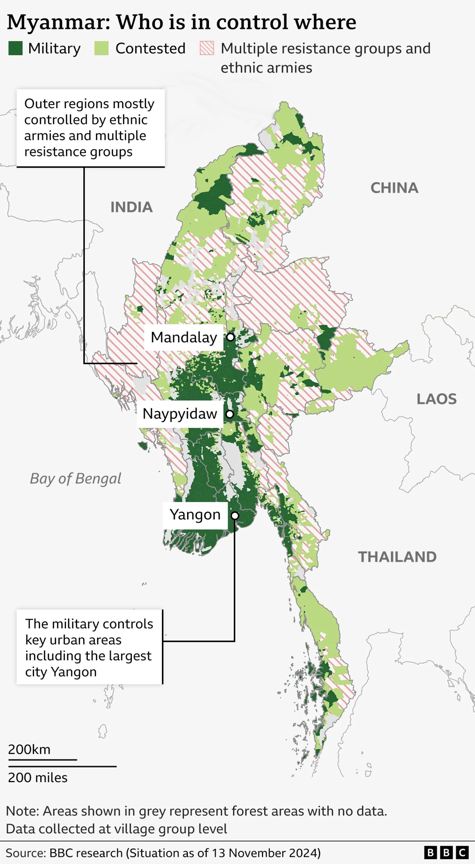

According to a report from late last year, ethnic armed groups and resistance organizations control 42% of the country's territory. The junta still holds major cities, while the remaining areas are contested, with stalemates persisting. For ordinary people, even basic communication with families and friends is difficult. In areas not under control, the military enforces a "four-cut" policy, targeting food, finances, intelligence and recruits recruitment. Internet connectivity is unstable due to damaged infrastructure and deliberate signal jamming. Even in junta-controlled areas, blackouts lasting half a day are common due to foreign investment withdrawing from energy and telecom sectors, forcing people to adjust their daily routines around electricity availability.

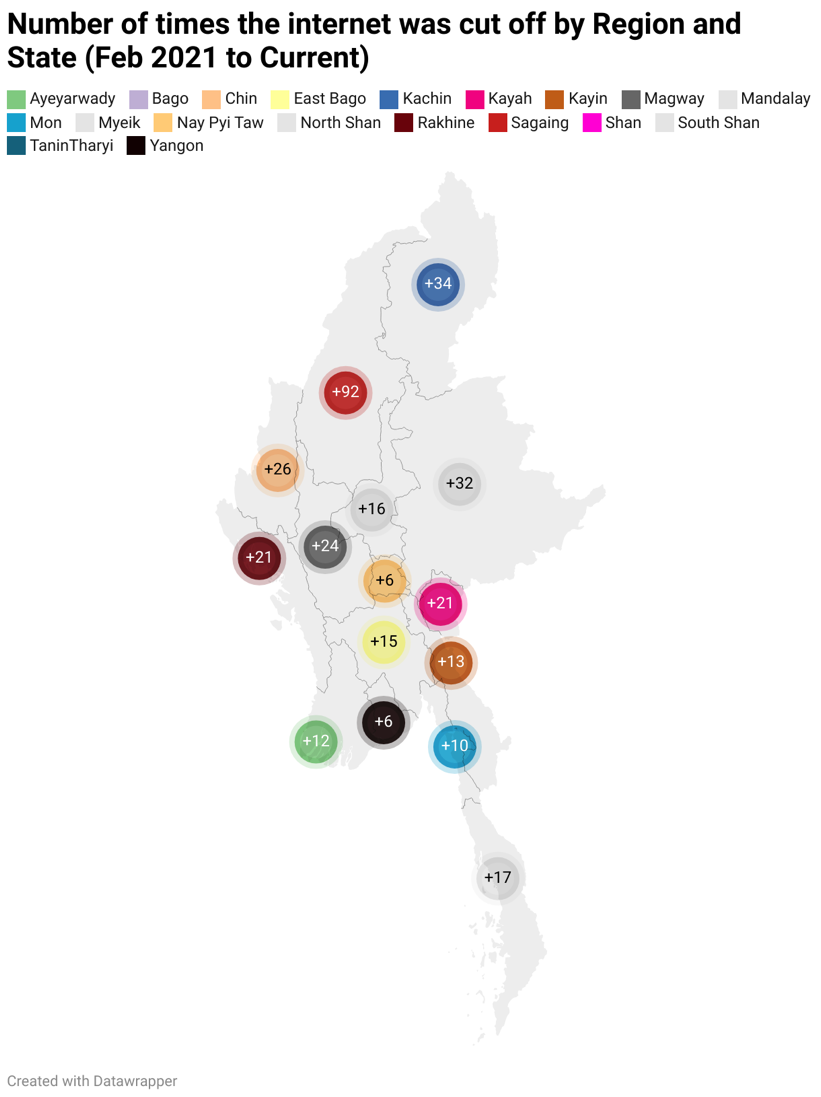

After a colleague was arrested, Bradley left Myanmar. From a relatively safe environment, he decided to continue tracking the country's internet control policies with his colleagues, joining the Myanmar Internet Project. Bradley told me that internet censorship isn't limited to signal jamming— mainstream social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram were immediately banned after the coup. Telegram remains unblocked, as the junta relies on it for propaganda. Constant surveillance is even more dangerous: posting anti-junta content on social media can lead to doxing and arrest. Since 2021, the junta declared the use of virtual private networks (VPNs) illegal. Six months ago, VPNs services began to be blocked, suggesting the military government has advanced in surveillance technologies. Earlier this year, new laws imposed one to six months of imprisonment or fines for installing or providing such services

Another target of surveillance and interception are payment and transfer channels. The junta has modified laws and enforced KYC (Know Your Customer) requirements, bringing mobile payment accounts like KBZ Pay and Wave under surveillance. Suspicious accounts can be frozen without notice, and the military raids registered addresses within six months as a common pattern. Journalists, dissidents, and resistance groups seeking funds have reportedly faced such measures. Kyat's depreciation has exacerbated inflation: while the official exchange rate is ‘maintained’ at 1 USD to 2,100 kyat, the black-market rate has soared to around 1 USD to 5,000 kyat, with banks limiting withdrawals. What the junta earns from oil and gas goes to the military at the expense of other basic services. Prices for necessities like medicine are rising, and capital continues to flee Myanmar, as shown by Burmese becoming the second-largest foreign buyers of Thai condos after Chinese.

Mobile wallets and bank accounts now impose new electronic IDs (e-IDs) and mandatory SIM card registrations. Under the Counter-Terrorism Law and Cybersecurity Law, authorities can investigate, control, block and shut down digital platform services and electronic information, as well as order "interception, blocking, and restriction" of mobile and electronic communications or "location verification". Except for SIM card registration, these policies were all introduced gradually after the coup. As a result, the identity verification system is a crucial link in the surveillance chain. Some cannot access communication or banking services due to missing or lost government-issued ID—a flimsy, bendable paper card—others face danger due to their ethnicity, occupation, or address listed on them.

When Bradley shared this with me, we sat in a hallway of a Devcon side event. Speakers inside are discussing a new societal framework based on blockchain: on-chain identities, on-chain wealth, on-chain sovereignty. The world seems to be moving forward, while Myanmar remained mired in civil war—it is an ultimate kind of FOMO (fear of missing out). "I feel like we (Myanmar people and the global crypto community) fit spiritually, but not practically," Bradley gave a wry smile. "At least when I discuss this with my friends, our conversation always ends with: 'there’re still blackouts'."

Myanmar's Internet History: Great Leap and Devastating Plunge

Amid the overwhelming narratives of disaster, it's easy to forget Myanmar in the previous decade. Starting in late 2010, the country underwent democratic reforms. Lifting internet restrictions and liberalizing the telecom industry, Myanmar went from having a lower mobile phone penetration rate than North Korea to becoming one of the most mobile internet and smartphone-savvy developing countries, with SIM card prices dropped from $2,000 to $1.50, and smartphones became affordable at around $20. Norwegian company Telenor and Qatar-based company Ooredoo became authorized telecon operators, breaking the monopoly of state-owned MPT (Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications). Thousands of cell towers sprang up in forests and remote rice fields. In just six years, nearly everyone had access to mobile internet. Because most people knew little about the internet before this, it was common at the time to equate Gmail with email and Facebook with the internet itself.

During that period, Myanmar was seen as a new, opportunity-rich testing ground for the internet. Htway had returned from abroad to work at an ICT startup hub in downtown Yangon. In a 2016 public speech, he expressed confidence in Myanmar's internet future: "Hacking means solving problems creatively... (In that sense) we are nation of hackers," he said. "We have to become citizens who are empowered by technology. We are still divided in this country along the lines of class, privilege, wealth, language, religion and all kinds of other things. But we are also hackers who had hacked buses, Facebook and a million other things to make things more useful to ourselves. Now it’s time for us to hack our democracy." Many developers sought to address the practical problems emerging from Myanmar's rapid transformation.

Despite numerous opportunities brought by internet openness, the struggle over internet access between people and the government persisted. In 2019, the NLD government imposed a large-scale internet shutdown in Rakhine State to combat ethnic armed groups, widely reported as the world's longest internet shutdown, affecting around 1.4 million people. During the pandemic, the lack of internet made it difficult to disseminate basic medical and emergency information. Bradley and his colleagues protested this shutdown, but when they approached the authorities, an official told them, "They have 2G." What disappointed Bradley even more was that many didn't support their protest. "A friend said to me that Rakhine people are terrorists, are trouble making people," he recalled.

The coup halted Myanmar's internet development once again. Amid widespread opposition, Telenor and Ooredoo sold their Myanmar subsidiaries to companies with potential ties to the junta in 2021, exposing vast amounts of user data to surveillance. The remaining telecom operators, MPT and Mytel, are under junta control. Resistance groups have targeted telecom towers to disrupt military communications and revenue, while the junta's internet blocking and surveillance have grown increasingly sophisticated. As of last July, 291 internet shutdowns had been recorded nationwide, with 80 of Myanmar's 330 townships completely cut off from the outside world.

People still strive to maintain basic internet connectivity. Some local ISPs (internet service providers) refuse to enforce shutdown orders due to economic losses. Additionally, Starlink-equipped internet cafes, offering connections for 500-1,000 kyat (about 10-20 cents) per hour, provide essential internet access. The Myanmar Internet Project estimates over 3,000 Starlink dishes are now operational nationwide, used by civilians, rebels, and even scammers. Reportedly, a tweet by David Eubank, a relief organization leader on the Myanmar border, thanking Elon Musk for Starlink, increased awareness of this service. However, since Myanmar isn't on Starlink's official coverage, SpaceX could cut off roaming services, as it had done before in South Africa and Cameroon.

Starlink cafes are often equipped with bomb shelters, as frequent airstrikes on civilian facilities by the military have become common knowledge. People share checkpoint and troop locations, or airport activity, on the ‘Scout Channels’ in Telegram. The limited connectivity still offers civilians a chance to stay informed and avoid danger.

In an Exiled Life

"There was once a bomb landed 100 meters away from me," said Mar, a Myanmar photojournalist. "But now no media wants pictures of airstrikes anymore—they're too common." Many independent journalists have chosen exile over silence and control. However, they return frequently to report. Mar's reports and photos are often sent via Starlink cafes. When we spoke, he had just recovered from malaria contracted in the rainforest. These journalists have produced impactful work from the frontlines of war and scam centers, including winning the World Press Photo award consecutively in 2022 and 2023. At the same time, their reality mirrors that of many Myanmar exiles, where technologies can find potential application scenarios.

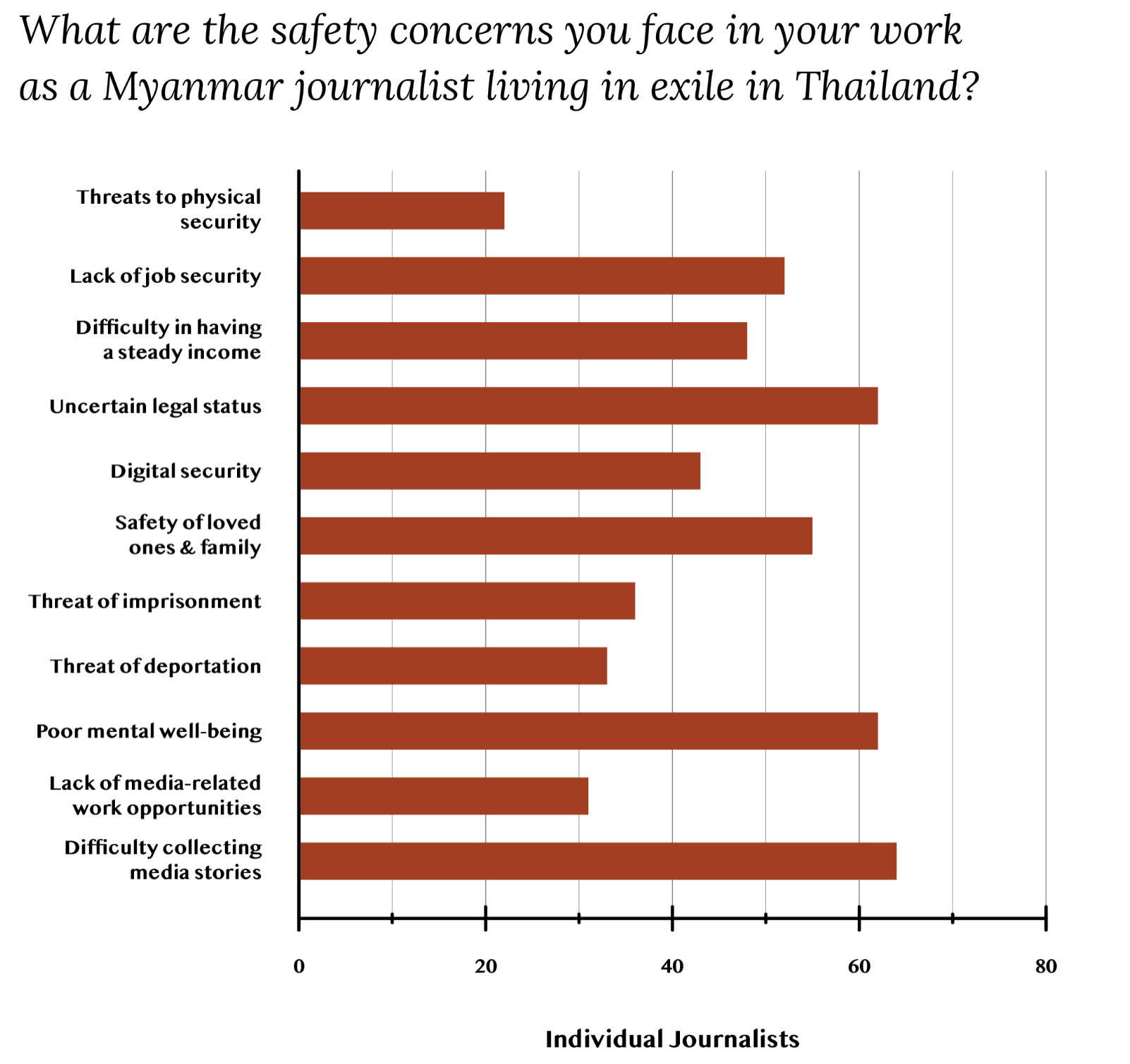

Soon after the coup, the junta began revoking media licenses, arresting journalists, and raiding media offices. Since the coup, seven journalists and media workers have been executed, and at least 150 have been arrested and imprisoned. Amendment to Section 505(a) criminalized comments that "cause fear", spread "false news, [or] agitates directly or indirectly a criminal offense against a Government employee". In the 2024 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders, Myanmar was listed among the top ten most dangerous countries for journalists. This has led to a mass exodus of journalists to neighboring countries. Mar typically shuttles between Myanmar and Thailand every three months, as he must report to the Thai immigration department regularly.

A few can afford to apply for two-year education visas costing $12,000-$13,000 or obtain tourist visas from other countries. Lay, a university dropout, left for Laos in March 2024 to escape the junta's forced conscription. With the help of a Burmese intermediary, he obtained a Thai tourist visa and now works as a waiter earning $300 a month. "That man used to be a doctor, but now he makes a lot of money arranging visas," Lay told me.

For most Myanmar journalists in Thailand, however, the options are limited: register as refugees, lose their passports, and be resettled in countries like the U.S. or Australia; or pay exorbitant fees for temporary work permits (pink card). Due to the limited capacity of exile news agencies and the requirement to require permission from local employer, some journalists end up working as waiters or blue-collar workers. "We had one journalist who had 15 years of experience as a reporter in Myanmar, when he came across the border into Thailand, he had to take on work as a welder. Like fixing cars and stuff like that." said Kyi from Exile Hub, an NGO supporting exiled journalists and activists. Exile Hub has provided fellowships, short-term shelters, trainings and mental health consulting to 2,100 people.

Exile Hub also began during the coup. Kyi, as a former media producer, initially sourced and distributed safety helmets, press vests, and foreign SIM cards with data roaming with her peers. When police opened fire on protesters and targeted journalists, they shifted to safety and first aid training. As more people were forced to flee, they began raising funds through PayPal to cover airfare, quarantine hotels, and temporary housing during the pandemic.

In following months of the coup, some journalists "gambled" on leaving through airports, as the customs, immigration, and local police databases weren't yet synchronized. But "a lot of journalists who are over the age of 30 had to get a new ID card as an adult, (which) will say their profession as journalists. And then they're screwed," Kyi said. Htway also told me that "Some people, they don't even have a passport, or they might have a passport, but it might need to be renewed—In Myanmar, passports are only valid for five years. As you know, if you have only six months left, you can't travel." As a result, most must cross borders on foot, and every return carries the risk of arrest, forcing families to live apart for long periods. On top of this, the threat of deportation looms constantly.

Beyond identity issues, there’re financial challenges. Many interviewees and a relevant report indicate that exiled journalists in Thailand earn a rough average of $200 a month. Additionally, anti-money laundering policies make it nearly impossible for Burmese refugees to open Thai bank accounts. Many independent media or organizations like Exile Hub rely on donations and international aid. However, these funds often come with restrictions and bureaucracy, rarely reaching journalists directly. On the other hand, while many journalists are willing to forgo bylines for safety, funding requirements force them to prove their journalistic work, creating a paradoxical dilemma.

"I really wish that people had developed the ZK proofs better for Myanmar use cases. And I really wish the crypto end point delivery system worked in Myanmar because it would make my life a lot easier," Kyi said. "But at this point, I can't justify to any of our donors for doing this because, I mean, look at it. It doesn't work yet... It's really tough fundraising for something like this, because a lot of times I think nowadays people don't believe in press freedom around the world, the faith in journalism and media as an institution is eroding... People are doing journalism not because they think they can get rich off it, but because it is revolutionary creative labor. They're doing work to support the true and accurate production of information and facts coming out from Myanmar. And I don't like a lot of the journalists within our communities not being paid very well. They're not being compensated for their contribution to the revolution."

Facilitating Money Flow: The Hundi System and Crypto Adoption

In the absence of banking services and under tight control of money transfers, much of Myanmar's financial flow, including international aid, relies on the ‘Hundi’ system. This term refers to an informal financial service industry originating in 12th-century India—a network of transfers and payments based almost entirely on trust and personal relationships. "If I want to send money to my dad, I need to find a Hundi in Chiang Mai, give them his information, and hope the money arrives," Htway said. "It usually does."

Hundi system has long been part of life in Myanmar. "Everyone knows a Hundi" is a common refrain among interviewees. A 'typical' Hundi is often a wealthy elder Indian, running other businesses like restaurants, grocery stores, or import-export shops. "A lot of Indians, but also Chinese and Burmese... (including) young people announcing their services on Facebook. You can borrow money from them, they're like banks... people with a Thai account can become hundis. And recently they adopted crypto." said Ni, a Myanmar researcher specializing in financial consulting.

Ni's work involves helping organizations moving money into Myanmar, as he knows many Hundis. "But the Hundi system is notoriously not transparent, ask different exchange rate up to 8%... you have to negotiate with people to get exchange rate, and its competitive market now," Ni shared. He recounted a recent infamous anecdote: traditional Hundis are often hesitant to handle the paperwork required by NGOs, which led a Frenchman to see an opportunity. He became a Hundi and took on much of this work. However, he stopped responding while processing a large aid payment.

The junta has tried to control money flows outside the banking system, making it illegal to act as a Hundi or trade cryptocurrencies. Meanwhile, the opposition National Unity Government (NUG) has recognized Tether (USDT) as official currency since late 2021. "(For) 3 years they try to block other ways of money transfer but people still do it, they try to track down but they are not good at it," Ni said. Still, some have had their bank accounts frozen for buying crypto, as there might be "intelligence pretending as P2P exchanger".

About nine months ago, Binance's app and website were blocked by the junta—much like Facebook, many Burmese equate Binance with crypto itself. Similar to internet development, Myanmar skipped credit and debit cards, transitioning directly from cash to mobile payments. By 2019, mobile wallet penetration had reached an astonishing 80%. These circumstances lead people like Ni to believe that cryptocurrency can gain wider adoption in Myanmar. "Part of my job is urging doners and training people to use crypto. It’s a cheaper, efficient, payment with fix-change rate... my friend translated wallets into Burmese."

In fact, Myanmar's chaotic situation has spawned many crypto-related projects and applications. In 2022, the NUG launched the Digital Myanmar Kyat (DMMK) and NUG Pay on the Stellar Blockchain. Coala Pay, another tool developed by team members from Myanmar, aims to deliver international aid directly to local organizations and facilitate daily transactions among refugees using stablecoins and simple interface. Though not directly related to currency, Rohingya Project, briefly showcased at Devcon 2024, aims to verify and grant on-chain identities to the Rohingya community via social networks.

Sin, a crypto industry consultant, helps overseas companies pay Myanmar employees in crypto. "These companies have no other channels to pay, so they have to use crypto," Sin said. "My clients typically earn around $400 a month... With crypto, they can save money to eventually leave Myanmar." Sin hopes not only to help people acquire crypto but also see them starting to use it. That said, many still associate crypto with crime and scams. "(After the coup,) actually a lot of (wealthy) people try to put their money in crypto out of desperation, not because they understood it... My friends were telling me a lot of people lost money in Luna, " Htway said. Recent reports also indicate crypto is widely used in the scam industry along Myanmar's borders.

"It would be very beneficial with crypto adoption, but who will do it? Business don’t have enough profit. NUG do it, but their crypto stuff is useless, they don’t get the potential of crypto. NGO’s doing it but in very small scale. This is not just technical solutions, but also political issue and capital issue. I don’t know who is capable of doing it and willing to take political risk at the same time," said Ni.

Epilogue

February 1st 2025 marked the fourth year of Myanmar's military coup. As usual, the junta has extended the state of emergency for another six months, pushing the deadline for holding a general election to restore civilian rule to January 1st, 2026. "The outcome might be that we win the revolution. Everyone decides to form a federal democracy. We all live together happily ever after, possibly,'" Kyi said. "But if that doesn't happen, and it's likely that won't happen. We still need to have people who can speak the truth. We still need institutions who will stand up for freedom and justice. We still need to be able to see a more democratic way of organizing and operating.’

From the wounds of civil war and the junta's oppressive policies, Myanmar's people are naturally drawn to blockchain and encryption technology. Despite certain infrastructural obstacles, numerous use cases like providing financial services, countering inflation, resisting censorship or verifying identity and informal education... Lots of Burmese use end-to-end encrypted communication apps. They are enthusiastic about blockchain adoption, while scrutinizing it with a clear, pragmatic and cautious perspective on the fringe of the crypto world.

With extremely high penetration rate, digital technology fuels optimistic visions of the future for many Burmese. As Bradley put it, "How much worse can it get?" He recalled the friend who initially opposed his protests: as the civil war began, ethnic armed groups, including those in Rakhine, quickly became key forces resisting the junta, that friend did come to Bradley and apologize for his remarks. Ethnic divisions seemed to fade a little in the face of a common enemy. "We'll become Asian Wakanda!" Bradley believes.

During our interview, Mar shared some recent photos from his reporting: a makeshift village in the rainforest, where people slept huddled in bomb shelter cave each night. "Everything here gets worse, these people have nothing," Mar said, pointing to the village. Then he scrolled to a photo of himself teaching children sun-print (a cheap camera-less photography using sun to create image). I easily associated this moment with the code "look up at the sky" from Bradley’s story—For over four years, many things have fallen from the sky: the coup, bombs, surveillance, satellite signals, news of their loved ones, freedom... Much like those children discovering sunlight on fabric, while the sky seems empty most of the time, it may hold a different vision for those who are looking.

(Some interviewees in this article are given pseudonyms)

Discussion