Crypto Flight Vol.11 | Do Runaway Tsinghua Ren Dream of a Bitcoin-Standard World? Interview with Hu Yilin

“The political trajectory of the real world turned against them, but their ideals didn’t change.”

The Local Rhythm of Singapore

Beginning and Continuation of Philosophy

The Politicization of Encrypted Reality

Encrypted New World: A Pluralist Solution from Blockchain

Rectification of a Post-Store-of-Value Era

The Many Faces of the Crypto World: Memecoins, Trump Coins, AI

💡Reporter's note

When it comes to naming thought leaders and veteran players in the Chinese-speaking crypto world, Hu Yilin — who once taught philosophy of technology at Tsinghua University — is an unavoidable figure. I first met Professor Hu at the Bitcoin Summit in Singapore last March. Later that month, we arranged to meet again on a scorching afternoon in Geylang. We wandered the streets and eventually found a café, where we chatted for two hours about everything under the sun. But both Bitcoin and the broader world of crypto evolve at lightning speed, and by the time our initial interview could have been published, the moment had passed.

Later, I learned that it was precisely that exploratory trip to Singapore that solidified Professor Hu’s decision to leave his academic position at Tsinghua and move his entire family to Southeast Asia. When news of his relocation arrived in December last year, it stirred quite a bit of discussion in the crypto community. At a historical juncture when crypto is facing dramatic external shifts, filled with both opportunity and risk, my collaborator 935 and I decided it was time to fly to Singapore again for a follow-up visit. In mid-February, we conducted two in-depth interview sessions with Professor Hu, totaling six hours. We pulled our focus away from the then-booming crypto prices to start with his personal decision to move south, eventually diving into the question of where diasporic Chinese might find their path in a new era of (de)globalization, interrogating the ideals of Bitcoin maximalism, and tracing the technological philosophy underpinning it all. Professor Hu’s insights into common questions always offer a refreshing perspective.

Before our first interview, we treated Professor Hu to a local Singaporean specialty — bak kut teh. Before the second session, he returned the gesture by treating us to Chinese-style frog porridge. The fusion of Singaporean and Chinese flavors lingered on our taste buds, echoing the intellectual sparks from our conversations, leaving us with a deep sense of nostalgia.

Just over a month has passed since then, and the crypto market has already undergone seismic changes. Many narratives have collapsed, and industry leaders once hailed as deities have come crashing down to earth. Yet looking back at the transcripts, Professor Hu’s thinking — grounded in the most fundamental logic — rekindles our sense of conviction.

About

Hu Yilin

Former Associate Professor in the Department of History of Science at Tsinghua University.

Currently an independent scholar, initiator of CNDAO, and founder of TIANYU ARTech Studio.

Flytoufu

Member of Uncommons.

935

Mind in the 20th century, body in the 21st century, spirit in the 22nd century crypto movement and philosophy of technology researcher.

The Local Rhythm of Singapore

Flytofu: Professor Hu, you officially relocated last December. What’s your current lifestyle like in Singapore?

Hu Yilin: I’ve basically found my rhythm here. Every morning I take my kid to kindergarten, then I relax a bit in the morning, get some work done in the afternoon, and in the evening I pick her up, have dinner with her, take her to the playground, then give her a bath and put her to bed. Thankfully, she’s adapted well.

Honestly, my schedule is almost too relaxed now. But I’m starting to ease back into a proper routine — I’ve restarted a reading group. Every Sunday night we meet in person to read Heidegger’s Being and Time, which I’m quite comfortable leading. I'm also hosting online reading sessions on Bernard Stiegler’s La misère symbolique (The Symbolic Misery). The first volume is about cinema, and the second about art. What Stiegler refers to as "symbolic misery" is the idea that the working class isn’t just materially impoverished, but spiritually as well. His thinking centers around the proletarianization of the mind — a form of spiritual impoverishment under capitalism. In a sense, it's a critique of capitalism.

Flytofu:Why did you choose Singapore over Hong Kong at the time?

Hu Yilin:The Shanghai lockdown was a turning point — it made the overall uncertainty and insecurity of the domestic environment more palpable. While I’m still optimistic about China’s long-term development — I believe the country can weather all kinds of crises — once you have a child, you begin to look at things differently. I wanted to give her a more stable and predictable environment.

Singapore doesn’t offer many other perks, but it is stable — like the climate here, evenly hot all year round. This predictability may not be great for innovation, but it’s exactly what you want when raising a child — "a boring kind of stability."I visited Hong Kong a few times, and the urban experience wasn’t great. Walking around the city felt suffocating, with tall buildings looming overhead. Even in Central, turn any corner and it’s just more glass facades — you can barely see a patch of sky during the day. Would that kind of environment affect a child’s development? Would growing up in such cramped spaces make one psychologically repressed?

Singapore is different — it’s more open and spacious, full of vitality and life. The “garden city” reputation is well-deserved — greenery is everywhere, and you can see the horizon even in the city center. No matter how busy a place is, there are always tall trees, lawns, parks, and nature reserves. Even between buildings, there are plants growing in the sky. In Hong Kong, I often felt like shop assistants looked grumpy, like everyone owed them money. In Singapore, even when I stammer through my English, they happily switch to Mandarin and greet me warmly. Of course, maybe I just got lucky — both of my visits to Singapore were quite pleasant. But maybe that’s what fate is.

Flytofu:These days, overseas Chinese can stay more connected to China through Chinese apps. For example, one can look up travel tips on Xiaohongshu. Do you think that’s an advantage? Or does it create a kind of distance from the local environment in Singapore?

Hu Yilin:My wife uses those apps. I usually don’t use any guides — I just wander around and see what I find. I don't feel the need to look for anything too deliberately. When I was a kid in Shanghai, I used to just walk around and explore. It’s the same here — the hawker stalls have plenty of good food.

If I had to name one thing I’m still adjusting to, it’s the feeling that people here are a bit too laid-back. Singaporeans have great service attitudes, but sometimes it’s a bit clumsy or wooden. It doesn’t have the kind of sharp, savvy energy that comes from China’s highly competitive environment. In China, customers are picky and demanding, which forces service providers to be more precise. Here, things like home services, renovations, or appointments can take days to arrange. But if you’re willing to adapt to the slower pace, it’s actually fine.

Overall, I think it’s a good thing. The “distance” you mentioned is actually a condition for maintaining cultural diversity. We’re now in a state of both connection and separation. We're not fully synced with China, but not entirely cut off either. It’s the same with foreigners — this kind of in-between state allows for a relatively unique cultural independence.

Technology is actually the precondition for this. Using WeChat or Xiaohongshu is a bit like bumping into a fellow villager in a foreign land. In the old days, when we talked about fellow villagers, it meant shared memories and experiences — like how Shanghainese talk about Waibaidu Bridge, the Oriental Pearl Tower, or life in the alleyways. Everyone remembers how Suzhou Creek used to stink. Now, if you grew up with WeChat and I did too, then we’re like “new villagers” of the internet age.

Society today is losing the conditions that allow for separation. New Shanghai residents and new Beijing residents live in the exact same apartments and communicate the same way. How do we differentiate ourselves? So, in that sense, "the wall" isn’t entirely a bad thing — it allows China to develop an entirely independent ecosystem internally, which can grow first in isolation and then compete internationally. We need certain kinds of limits so that regional styles and identities can take shape.

Flytofu:How do you view the growing global mobility of Chinese people in this era? Many say it’s the rise of the diasporic Chinese.

Hu Yilin:That’s also part of the reason I started the Huawen DAO(“华文DAO“) — to revive Chinese culture overseas, even beyond the physical world. “Seek the rites in the wilderness when they’re lost in the center,” as the saying goes. Ironically, it’s mainland Chinese culture that’s now more closed-off and conservative.

All cultures are essentially hybrid. Today’s Western civilization was built from a mishmash of earlier ones — Greek, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Germanic, plus Arab and Indian influences, not to mention technologies and ideas from China. That’s what shaped what we now call the “West.” The ability to absorb diverse elements is key to maintaining cultural vitality.

The revival of Chinese culture today doesn’t mean simply restoring tradition. It’s about regenerating tradition, not reverting to the past, but giving it new life. That requires an international perspective — first affirming Western culture, then absorbing it. That’s what true revival means. I’ve said before that Singapore is an ideal place for this — a place where cultures blend, yet Chinese identity is preserved. Everything coexists in harmony here: you have people living Western-style lives, others living in traditional Chinese ways.

Diasporic Chinese today are similar — they don’t have to fully assimilate into local societies. They’re adding a new skin tone to America’s color palette, sure — but if they don’t also bring in new cultural perspectives, then they’re not really contributing. True diversity, inclusivity, and uniqueness should be cultural — not just about the biological diversity of human beings as animals.

Beginning and Continuation of Philosophy

Flytofu: Professor Hu, you really should write a reader’s guide to Heidegger. I’ve often heard people say Singapore is a cultural desert. Being and Time is such an abstruse original philosophical text—how do local audiences in Singapore respond to it?

Hu Yilun:A reader’s guide doesn’t carry much value—philosophy books need to be read in their original form. A guide is like chewing gum that’s already been chewed—there’s no flavor left. The joy of philosophy lies in the chewing process itself. Successfully understanding a seemingly difficult book brings a great sense of accomplishment, and also gives you the courage to delve deeper into philosophy. Many people shy away from the difficulty and turn to introductory books, but that totally misses the point of thinking. It’s like chewing on sugarcane and only swallowing the dregs—that’s putting the cart before the horse. The conclusions of philosophical books are usually the dullest part. For me, the book that truly initiated my philosophical awakening was Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Once you understand it and feel its internal coherence, you realize why it needs to be so obscure—and you begin to grasp what it’s truly concerned with.

The participants in my reading group aren’t usually native Singaporeans; most are international students or folks from China exploring new paths. And actually, these philosophical texts are quite beginner-friendly. They don’t require a ton of prior knowledge—classic philosophical works all start from basic human conditions and life experiences, aiming to help you answer your own questions. Anyone who has grappled with life and death, who has lived and experienced life, should be able to enter into philosophical thought. Heidegger’s Being and Time is quite pure in that sense—it's directly about the question of “Being,” which actually makes it more accessible for beginners.

The difficulty lies first in shedding your fixed mental patterns. Modern people have been reshaped by rationalization, technology, and social environments—we unconsciously think in instrumental and conditioned ways. These patterns are very goal-oriented. When philosophy talks about “freedom” or “authenticity,” many people don’t get it because their thinking is linear and focused on what can be seen and touched. But the most important things in life—like life and death—are precisely not linear. You can point to someone taking their last breath and call that “death,” but that’s not the same as the death you fear. The external, objectified concept of death isn’t the same as the death you truly face. Your lived experience—such as the inner sense of being alive—is more intimate and direct than external objects. Our everyday language system revolves around external things, so we struggle to switch into introspective thinking, and that’s why philosophy seems obscure.

The second difficulty is language itself. To help readers break free from fixed thinking, philosophers have to reinvent the language game. Traditional vocabulary traps you in habitual thinking, so they invent new terms to give you new tools. It’s like using a smartphone for the first time—you fumble at first, but once you get the hang of it, you realize it’s powerful. Philosophical language works the same way.

Flytofu: I used to think you focused mainly on the philosophy of science, but it seems like you have deep engagement with philosophy as a whole?

Hu Yilun: I’ve always believed philosophy shouldn’t be divided into subfields. The fundamental questions of philosophy—life and death, being—are inherently unified. Because we’re a whole person, philosophy is about “knowing yourself,” and the “self” isn’t a machine that can be broken down into assembly-line parts: wheel here, frame there, steering wheel, engine, seat... finally assembled into a car. That’s not how humans work.

When reflecting on technological or political issues in society, sure, you can treat them objectively and assign different teams to study each part—technology here, politics there, ethics somewhere else—as if stitching together a complete philosophy. But the product of philosophy isn’t a machine—it’s you. Can you really “assemble” yourself?

Technology and politics exist because they are elements within every individual. To understand yourself, you must ask: What kind of person am I? Where do my mental habits come from? What’s my lifestyle and way of being? These questions inevitably lead you to consider the era you live in—is it the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, the Industrial Age, the Electrical Age, or the Information Age? Technology is not a detachable component but part of the environment that defines us. Ethics, aesthetics, and all other domains ultimately converge into the unified personality of “you.” You don’t feel fragmented.

Philosophy, in its purest form, pursues this unity. Its object has always been “Being as Being,” the single, fundamental question. “Philosophy of technology” is just an academic label. In the academic-industrial complex, I had to pick a workstation, publish papers, apply for grants—so I slapped on the label “History and Philosophy of Science.” But as a free individual, I don’t carry any label. I face only the most fundamental philosophical problems.

Flytofu:This seems to circle back to the very first question—why did you give up a prestigious position at Tsinghua University? Many people see that as a bold leap. Was it in pursuit of a more holistic and self-consistent way of life?

Hu Yilun:First of all, it was a personal life choice—not something with a grand meaning. I’ve always emphasized “unity of knowledge and action,” and this is just another form of that. My material needs are modest. At my current level of desire, I don’t need to worry about basic survival. So the question becomes: if you don’t need to think about making a living, what kind of work would you choose?

In the AI era, this is a crucial question. If the world goes the way optimists imagine—where AI gradually takes over human labor and liberates people from economic survival—then the next question is: what do we do? Do we just lie around like pigs, waiting to be fed, muddling through life? Or do we build something, and choose a way of life that belongs to us? Once money isn’t a concern, a job at Tsinghua doesn’t help me much anymore—it’s just a title. Maybe it makes people respect me more, but if someone respects me only for the title, I probably wouldn’t respect them either. That’s a kind of filter. Without a title, I can still teach, run reading groups, and give lectures. I’m planning to launch online courses and re-record all my Tsinghua classes.

Flytofu:When you decided to leave Tsinghua, did Professor Wu Guosheng try to persuade you to stay?

Hu Yilun:Professor Wu didn’t try to stop me. His philosophy has always been to respect our freedom. He treats students as individuals and never sees them as workhorses. Other professors assign topics and tasks, making students do this and that—Professor Wu never did that. We never even co-authored papers—everyone wrote their own. When I told him, he didn’t try to keep me, because he trusted I had thought it through. Of course, he did worry about who would take over the philosophy of technology area after I left.

935:I’m curious—at what point did you begin to integrate your inner drive, the things you truly wanted to accomplish, with philosophy of science and technology?

Hu Yilin:There were a few key turning points. The first was in high school. I was in a national science class, and just getting in meant I had a guaranteed recommendation to university, so I knew in my first year that I wouldn’t have to take the college entrance exam. As a result, my high school life was quite relaxed, which gave me the freedom to explore many extracurricular interests. The biggest influence at the time was the First Cause Book Series, such as A Brief History of Time. I also read Kip Thorne’s much thicker Black Holes and Time Warps, and various other popular science books on quantum mechanics. After reading a lot of these, my interests shifted toward the big questions—like the ontological question I just mentioned: what is science?

Back then, I was bold and fearless, writing a lot of philosophical essays, even calling them “papers” and such. This “neglect of proper studies” did indeed affect my performance in academic competitions. I initially insisted on applying to math or physics programs, but my teachers said I wasn’t good enough for physics based on competition results. They then suggested philosophy. I thought about it—philosophy could be a viable path. By that time, I had already started to pivot toward the humanities, and by a twist of fate, I ended up in the Philosophy Department at Peking University. That was the first major turning point.

The next time I really felt the charm of philosophy was in two stages. First was in the classes of Chinese philosophy professors like Yang Lihua and Zhang Xianglong. They were living, breathing Confucian scholars—people who seemed to have stepped out of ancient texts. Even though I didn’t agree with their views—I’m quite Westernized and liberal at heart—their charisma lay in the firmness of their character. You could tell they truly believed what they taught, and they could argue their points coherently.

They didn’t “convert” me—I still lean toward liberalism—but I learned to sympathize with Confucianism. A lot of people go through life never encountering someone they disagree with but respect. These classes taught me that intellectual difference itself can be precious. Isn’t this what the now-stigmatized “public intellectual” is supposed to do? To offer different perspectives, not just go with the flow? That helped me truly appreciate the value of being a scholar.

The next major moment was reading Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. The teachers at school were already impressive, but when compared to the greatest philosophers in history, there’s still a gap. Kant made me realize the depth human thought can reach. Reading him felt like that scene in One Piece where Roger says, “I left all my treasure there”—like he was telling me: “The Grand Line is out there. Go find it!”

A philosopher’s treasure trove of thought can’t give you direct answers, but it proves that achieving the highest level of self-understanding is possible. Kant showed the possibility of intellectual fulfillment, even if I don’t completely agree with his system. Heidegger served as a transitional figure. I respected my earlier teachers but didn’t agree with them, while Heidegger’s thinking resonated more with me, allowing me to follow his framework and continue developing my own philosophical style.

Later, during my graduate studies while working on my doctoral dissertation in media philosophy, I happened to see news about Bitcoin crashing. That led me to try applying media philosophy to understand what money really is. The mainstream criticism of cryptocurrencies is that they lack physical backing or endorsement. But currency itself is a virtual medium—what matters is the real transactional behavior it facilitates. That, I believe, is the true essence of money.

Bitcoin may be virtual and intangible, but as a medium of exchange, it’s entirely real. In some sense, Bitcoin is even more deterministic than the US dollar. I started pondering a basic question: what is virtual currency? Isn’t the dollar the real virtual currency? Because the total amount of fiat money can’t be clearly stated—it’s created through the money multiplier, layer upon layer. The Fed can print money whenever it wants, and the issued money can just as easily vanish again—like a dream or illusion. In this light, isn’t the dollar more virtual? A single movement of the Fed’s mouth—shifting a decimal point here, adding a digit there—can change the entire money supply in the market. Isn’t that the real dreamlike bubble?

That line of thought became the starting point for my deeper research into Bitcoin and blockchain. Later, I gradually connected the cryptographic movement to critiques of modernity—such as issues of human alienation in modern society and the dilemma of technological domination. These concerns could all find responses within cryptographic technology. That became the central thread of my later research.

Another turning point came after finishing my postdoc, when I was looking for a job. I was preparing to teach at Shanghai Normal University, but my tutor, Professor Wu Guosheng, had just moved from Peking University to Tsinghua and asked me to join him. That’s how I ended up in the History of Science department at Tsinghua.

Although I officially shifted into the history of technology, in essence, I’m still doing philosophy of technology. Studying the history of technology is very much in line with Heidegger’s philosophy. Heidegger emphasized human “facticity”—that to understand oneself, one must return to the historical context. As he put it: people are not abstract beings floating in a vacuum, but are rooted in specific historical soil. So studying the history of science and technology actually brings me closer to the essence of philosophy: to understand technology, you must first understand how it came to be historically.

The Politicization of Encrypted Reality

935:Speaking of technology in history, let’s talk about encryption. If we look back to the early days of the technology—the 1970s and '80s when civilian cryptography was born and began to develop—it was actually a very pragmatic and purely technical matter. But did it become politicized at some stage?

Hu Yilin:It wasn’t so much the politicization of technology as it was the politicization of the real world. This politicization began with digital currency—not the ideal digital currency imagined by cryptographers, but rather Alipay, digital banking, electronic credit cards—the trend of monetary digitalization. In the 1990s, stock exchanges weren’t yet digitalized; people still watched the boards in person. By the late '90s, digitalization of trading accelerated rapidly, and the trend that was once a concern became reality. In the '80s, this wasn’t yet a political movement—there were just ideals and worries, the foresight that privacy could be stripped away as information technology developed, and a need to prepare for this, to make IT compatible with individual privacy. If, in the future, society becomes digitalized and we still want to preserve personal privacy, then we should be able to use the tools we've prepared. In a sense, this is serving politics.

935:Would you say at that stage, they were mainly trying to solve a technical problem?

Hu Yilin:The reason they wanted to solve a technical problem was precisely because they had political ideals. If you believe society should be under panoptic surveillance, secured by the state and centrally monitored, then you wouldn’t think there’s a technical problem to be solved. That’s a political stance. Later, their political ideals were crushed, and the political trajectory of the real world turned against them—but their ideals didn’t change. They still believed in decentralized, free, and private transactions. So those ideals transformed into real-world political demands.

935:But it seems that during this process, there were certain points of rupture, moments when their political stance suddenly became radical. The cryptographers who first researched asymmetric encryption in the '60s and '70s had more of an engineer's pragmatic mindset—they were figuring out how cryptography could be used commercially by civilians. By the late '80s, civilian cryptography was elevated to the level of defending freedom of speech and even turned into a fierce resistance against any kind of centralized collective.

Hu Yilin:The entire history of the internet has always been political. ARPANET was born out of the Cold War, backed by the government to compete with Soviet technology. But the early internet pioneers were precisely liberals. They took military money but opposed control, emphasizing the free flow of information. Ideologically, they saw themselves as capitalist, not socialist; as technological romantics, not authoritarians or controllers. So the technical environment had to be decentralized and based on knowledge sharing.

Later, Bill Gates came forward and said programmers should be paid for their software. This went against the entire hacker culture at the time. Saying this back then was actually quite bold, because the mainstream belief emphasized that information should be free, open, shared, and not monopolized. A large number of developers, engineers, and participants opposed Bill Gates. They were shocked: how could information be treated as personal property rather than shared human knowledge? The internet has always been in conflict from the beginning. The spread of the internet’s TCP/IP protocol also relied on the open-source movement. At the time, there were competing protocols backed by different entities—like the UK’s postal service, France’s state-supported institution, and the Soviet Union’s centrally controlled system. TCP/IP, by contrast, was open. Because it was open-source and available to all, it became the mainstream.

ARPANET’s original concept came from a memo written by a chairman of a research institute: the idea of an intergalactic network, a future where information would be transmitted via computers, building a shared, transnational society. That ideal was there from the start—an internet with no borders, no center, a space where everyone could equally enjoy knowledge. The ideological trends within internet history have always carried strong political ideals.

935:In the crypto movement, the interaction between technical structures and human thoughts and desires shaped today's technical imagination. I think modern information cryptography relies on the entire infrastructure of information technology, just like the cypherpunk movement relied on internet culture movements.

Back in the Cold War era, centralized computing had a wholly negative image: massive bureaucratic systems that suppressed individuality—the very thing the counterculture wanted to resist. Later, microprocessors made personal computers possible, and suddenly, computers became tools that empowered individuals and promoted personal rights and freedoms.

The structure of the internet is also dual-natured. On one hand, it can be idealized as a flat, decentralized medium where all nodes are equal. On the other, its distributed structure also makes it an excellent vehicle for power penetration, a “panopticon” that can reach into the capillaries of society. So does a technical architecture inherently lead to a specific power structure?

Hu Yilin:On the one hand, technology is not neutral. On the other, people can influence its direction through their choices. If the internet had been developed in the Soviet Union instead of the U.S., it might have become a central nervous system for real-time control—perfect for implementing a planned economy. Luckily, it was initially driven by people who were relatively free.

935:Like the cyber-socialism that Chile’s Allende wanted to implement. So the internet itself is a dual-natured structure—it can be highly centralized or a symbol of freedom—depending on the will of those who shape it and the culture they cultivate?

Hu Yilin:Technology has multiple possibilities. The earliest computers looked huge, monopolized, hard to personalize or distribute. But the underlying logic of the technology still tended toward freedom. Turing’s fundamental contribution was the concept of universal computation. Computers are an abstract simulation of human calculation. How humans compute is how computers compute. And this computation can be standardly defined—every Turing machine is essentially the same, just with different computational power. In principle, they do the same thing.

Computing machines designed from this perspective have no secrets. The atomic bomb was shrouded in secrecy, but the early computing papers by Turing, von Neumann, Wiener, etc., were public. From the beginning, there was an emphasis on not monopolizing. Those with resources could build first, but others could do so whenever they had the means. The technology itself had a decentralized tendency. Even those giant early computers carried an inherent democratic potential.

Before the 1950s, many computers were specialized and customized. If computers had continued down that path, the future might have been: the U.S. government has a single computer, its technical parameters are secret, and others merely plug into it to provide information. You wouldn’t be allowed to build your own. But luckily, American culture itself leaned toward liberalism. While you can’t say early computing was entirely liberal, the entire information technology movement and liberalism supported each other and grew hand in hand.

Encrypted New World: A Pluralist Solution from Blockchain

935:Looking purely from the history of information technology, liberalism’s approach to technology selection—emphasizing free market competition and openness—has indeed brought us the benefits of widespread technological adoption. But from the perspective of a purely commodity-based economy, it also seems that a world shaped by neoliberal choices has distorted many aspects of our lives. For example, although we’re currently in an era of technological and economic prosperity, we also find ourselves in a spiritually and culturally barren time. So how should we understand the relationship between liberalism and modernity?

Hu Yilin:Cultural desertification, flattening, and superficiality aren’t the fault of liberalism per se, but problems inherent in modernity—whether liberal or authoritarian. Today, liberalism in the West is often equated with right-wing conservatism. But conservatism, ironically, emphasizes the protection of traditional culture. Liberalism doesn't inherently seek cultural flattening, atomization, or universalization. The emergence of cultural homogeneity signals that liberalism hasn't gone far enough—because freedom should extend beyond markets to thought itself. Both free markets and freedom of thought advocate for a rich and diverse marketplace. A market only exists when there are differences—only then can exchanges happen. Cultural plurality and the independence of local markets are part of the liberal ideal. The real question is: how do we resist the trend toward flattening? Liberalism should involve multidimensional markets.

935:So the flattening we see today isn't because we have too much market, but not enough? But isn’t the market itself fundamentally unidimensional—always optimizing for profit and efficiency—and isn’t that what causes the flattening?

Hu Yilin:That’s the narrow definition of the market—anchored to currency and commodities. But broadly speaking, there are also markets of thought and belief. Classical Western liberalism emphasized not the market per se, but freedom of speech, thought, and belief. This, in turn, led to cultural diversification. For example, the Protestant Reformation broke the monopoly on religious narratives. Everyone could believe in their own God, and churches could compete in a broader "belief market." The free flow of commodities is only one aspect of broader freedom.

Homogenization stems largely from capitalism’s Matthew effect. The pursuit of capital accumulation leads to "the strong getting stronger"—the more centralized production is, the more efficient it becomes; the more efficient it is, the faster it scales; and the more resources it captures. The end result is standardized, identical products. To restore diversity, we need ways to reconstruct pluralistic styles within the broader trends. That’s what I’m trying to explore—how blockchain could be a pluralist solution.

935:Since we’re living in this world, any new order or idea must confront the current conditions. If technology is to have real meaning, it must address present-day problems. We talked earlier about how the current situation may not stem from liberalism’s intentions, but perhaps from the structure of technology itself. While a free-spirited liberal atmosphere should encourage diversity, at least in the commodity market it seems we’ve fallen into a monocultural value system—one that appears to also dictate a singular culture. Can blockchain offer a way to crack this technical dilemma?

Hu Yilin:It can’t solve it directly, but it does offer a few layers of resistance:

The first layer is from overdrawing to saving, which is good for cultural diversity. Culture needs depth and accumulation; rapid iteration can’t foster diversity. If market competition is about who can overdraw the most, disregarding the past or experience and focusing only on storytelling, then the market remains overdraft-driven. But in a savings-oriented market, your ability to act is based on your accumulated capital. It’s harder to borrow based solely on new ideas—you need support from experienced investors. That makes it less likely that new players get instantly crushed.

Market homogenization is partly caused by the financing model. Once a new model works, it gets endless funding and rapidly expands, outpacing competitors before they can respond. If financing slows down, progress might be slower, but diversity increases. You have to expand step by step, and others can keep up. Of course, we still need patent protections—others need to differentiate, not copy. This leads to fragmented, pluralistic markets. Previously, slow expansion was seen as criminal—if you can scale fast, why hold back? Isn't that delaying human progress? But if we don't overdraw and walk step by step, human progress doesn’t actually slow—and debt must eventually be repaid.

The Second layer is the diverse token systems in blockchain. Traditionally, global diversity was maintained through national borders—different states and ethnicities created natural separations. In the internet age, especially with Web2.0 and giant platforms, these barriers collapsed. Now the internet has no terrain, no national boundaries, and even fewer language barriers, being dominated by English. Things that once sustained separation and diversity vanished—thus we got a flattened “global village.”

So how do we artificially recreate those barriers? First, through decentralized models. Social media today is driven by capital, which forces rapid expansion—no space for personal “backyards.” Old BBS forums still had some localism, but those faded because traditional platforms can’t support them economically—plus there’s regulatory pressure. Chinese forums basically can’t survive anymore; in the U.S., a few still hang on.

Another issue is the financial model. In the attention and influencer economy driven by big capital, a primary schooler might beat a graduate student—because they have more purchasing power, are easier to manipulate, and click more ads. Platforms designed with this business logic will trend toward flattening. Not only the content, but also people themselves become flat—everyone must appeal to the majority, not niche groups.

935:Is this forced expansion a form of technological inertia? To maintain the costs of running huge factories and machines, they must run day and night—humans must work round-the-clock, leading to mass production, which demands mass consumption, which in turn drives the need for new markets. Once we have machines and tech, are we also trapped in the inertia they bring?

Hu Yilin:Exactly. That’s efficiency-first ideology—everything is about capital accumulation and maximizing productivity. Why does blockchain offer a possibility? Conceptually, Web3 is still poorly defined, but fundamentally, it provides a permissionless, decentralized identity system under the user's full control. The most intuitive example is wallet-based login—you don’t register with an ID, your wallet becomes your identity, and you control it in a decentralized way.

This helps us return to the individual, rather than centering society around efficiency. Assembly lines make humans conform to machines. Humans become mechanical, and machines feel alive—running automatically. Workers are no longer full people, but just screwdrivers, sources of labor. Online, people become traffic—not full individuals, but sources of clicks. It’s the same as in a factory. You’re not participating as a complete self, but as a replaceable output.

So the key is reclaiming the right to define ourselves. If you don’t want to work in a factory, what do you do? You still need work, but all jobs require submitting to the dominant order. Unless your job is irreplaceable and highly personal, no one will hire you. No hiring algorithm can cater to individual uniqueness—it looks for general patterns. You say you're unique, but they can’t design a custom assembly line just for you—it shuts down when you leave.

How do we escape this? One path is new modes of production online. For example, digital nomads have, in some sense, broken away from traditional roles. In the past, everyone had a fixed role. Now, individuals have more autonomy. It may look like the gig economy, but in some ways it's a return to human nature. Even if the micro-work is still mechanical, you retain relative independence.

Digital nomadism is one model. Blockchain doesn’t directly bind to it, but strongly supports it. It lets you get paid across borders and receive salaries in crypto, bypassing geography. Web3 gives you self-sovereign identity. Traditional social media monopolizes users by locking identity to the platform—your accumulation is platform-controlled. Platforms constantly reset to optimize for new clicks, which contradicts user individuality.

So the question is: how do we take back our history from platforms? Platforms should serve real-time communication, but our digital footprints and relationships should be under our own control. Web3 may make this possible—platforms provide real-time interaction, but our focus is not on the platform-bound account, but on our blockchain identity. Even if I leave Twitter, you and I are still connected.

935:So you own your digital relationships.

Hu Yilin:Exactly. People should decide their relationships, not platforms. When a platform bans your account, both you and your followers are cut off. That’s why we rarely use niche platforms—they may collapse at any time. Early BBS data is mostly lost unless someone archived it. Relationships don’t migrate easily. If you’re going to hang yourself, you’d rather do it on a big tree. Today, individuals are fragmented, and platforms are unified. We need to reconstruct networked social ties, to force big platforms to change and make space for smaller, diverse ones.

The third layer is founding network states. Traditional states have physical borders and tariffs. Even small regions like Hong Kong or Macau, without strong geographical differences, maintain market independence via customs systems. Small nations need their own currencies for economic sovereignty. Previously, this was impossible—but with blockchain, it's feasible. Everyone can issue tokens, forming small, internally coherent economies they control. Influencer and fan economies already operate on internal logics.

If everything follows efficiency-first logic, then homogenization is inevitable—what’s most efficient wins. That kills diversity. The downside of platform economies is they depend entirely on major platforms. You give a streamer money, and 80% goes to the platform. It's opaque—just look at all the scandals around talent shows: scripting, manipulation. Blockchain solves this. A small group can organize around emotions or passion, independent of platforms, with open, transparent, and culturally rich economic systems.

935:Returning to small communities seems to be a growing consensus. More people are turning to local, nearby, familiar, or like-minded groups, trying gift economies, and rediscovering daily life with a human touch.

Hu Yilin:Yes. This community trend isn’t caused by blockchain, but blockchain supports and extends it into the digital world. In the wave of universalization, people still long for uniqueness and individuality. It’s a form of backlash, and blockchain helps it stabilize.

935:If we see crypto as one solution to break free from market logic—where are we now in that process? Are we ready to implement it?

Hu Yilin:I often use the metaphor of a New Continent to explain this. The first stage is when the digital New World appeared in the ’80s and ’90s with the rise of the internet. Humanity began shaping an independent digital realm. The second stage started as Blockchain emerged. Satoshi Nakamoto discovered the substance of this New World—it wasn’t just fantasy, but real, with actual, independent wealth. Then came the Gold Rush, everyone ran to mine resources in the New World and returned to the Old World to live. The rich consumed in the Old World but mined wildly in the New—lawless, chaotic, speculative.

Now the second stage has passed, and we've entered the third stage—the colonial stage. One thread involves people from the Old World sending administrators over; another involves the liberals of the New World gradually putting down roots. These liberals grow dissatisfied with the old order and want to establish a new one. At this point, the New World is no longer in a state of complete anarchy. Both threads are about the establishment of a new order—one seeks to extend the old order into the new realm, and the other seeks to overthrow the old and create something new. We're in just such a period now: the struggle has only recently become visible. Some want to impose the old model onto the blockchain world, while others want to forge a new path within it.

The next stage will be the independence movement—the New World breaking away from the control of the Old World, declaring its own independence. Right now, we are between the gold rush phase and the declaration of independence, a time in which various orders are still in conflict and struggle.

Rather than saying the New World is rich in resources, it’s more accurate to say it’s sought after because it is ownerless. Precisely because no one owns it, people can re-enclose land and rebuild order. The internet is also an ownerless space, originally without borders. So here too we see two tendencies. One is about governance: to assert that the internet does have borders, with more and more online platforms doing IP location checks. For those of us who admire the old-school hacker culture of the internet, this is almost intolerable. But this is essentially applying a traditional tariff model to internet governance.

The other tendency is represented by blockchain: to preserve the internet’s freedom. If regulators want to impose tariffs, then we simply don’t use fiat currency—we use native internet currencies to trade. Blockchain reinforces the ownerless nature of the internet.

935:Have there been any changes in the leading forces behind technological development? It still seems predominantly liberal.

Hu Yilin:There definitely have been changes, simply because more and more people are entering the space. It’s true that liberalism appears dominant—but that’s a retrospective view. Liberalism seems dominant now because it ended up being successful, so when we look back, we think it was always the dominant force.

In biology, there’s a phenomenon called genetic drift. In a relatively large ecosystem, genetic variation tends to occur randomly and remain relatively stable. Only those best adapted to the environment survive. But if a new environment is isolated and independent, and only a small group of organisms enters it, then the traits that proliferate may not have been the most competitive or mainstream in the larger ecosystem. They may have simply entered early or had some particular advantage that allowed them to thrive and reproduce in this new environment—thus amplifying certain genetic information.

We think of the U.S. as a Puritan country, with the Mayflower as the symbol of that culture. But the Puritan dominance in the Americas wasn’t because most of the settlers were Puritans—even on the Mayflower, nearly half weren’t. And before and after that voyage, many others migrated to America. So perhaps it was just a historical accident that shaped the cultural trajectory—an early advantage that was magnified and gradually solidified.

Liberalism likely entered the blockchain space at a particularly opportune moment. The rise of Bitcoin was largely driven by liberals, and its underlying architecture aligns well with liberal ideals. This was an early advantage, but it cannot be the decisive factor forever.

Ultimately, the prevailing ideology will have to be a new synthesis. Just as America, while originally led by Puritans, did not end up with a purely Puritan culture—it became a secular, independent, hybrid culture. The ideals of blockchain won’t end up being purely Austrian school, liberal, or anarchist either. Those early influences helped steer the initial direction and maintain its momentum, but in the end, it will have to compromise and merge into something new.

Rectification of a Post-Store-of-Value Era

935:

I've read your early articles on Bitcoin and agree that money is both instrumentalist and realist. From the instrumentalist perspective, the medium or substance doesn’t matter — anything that meets certain requirements can be a medium of exchange (money). From the realist view, I also agree that a deflationary currency like Bitcoin, with a limited supply, can serve as a store of value.

I want to look back at what problems Satoshi Nakamoto's original whitepaper fundamentally aimed to solve. Historically, if we look at this technology in the context of the time when the whitepaper was published, Satoshi mocked the fiat monetary system in the Genesis Block — highlighting endless devaluation and recurring financial crises. Among these, devaluation seems easier to address: a deflationary currency like Bitcoin can solve that.

But according to Marxist thinking, the root cause lies in structural contradictions in production and consumption. Economic crises are cyclical and might not be fundamentally related to what serves as money.So, even if we replace fiat with Bitcoin, isn’t it still impossible to prevent economic crises?

Hu Yilin:You say financial crises have nothing to do with money — that’s precisely what fiat currency supporters disagree with. Keynesianism was born in response to economic crises and gained respect as a way to solve them.

Why do Keynesians consider solving financial crises a merit of fiat? Because fiat allows for regulation. During deflation, you can inject liquidity; during inflation, you can tighten. The goal of monetary policy is to stabilize the market, preventing it from extreme booms and busts. Free market advocates believe the market will balance itself in the long run, but that could take years. Keynes responded by saying: “In the long run, we’re all dead.” We need to act when markets are imbalanced.

To recognize fiat is to recognize the regulatory role of money. Fiat theories believe that monetary policy can influence economic cycles. That’s not a Bitcoin theory. Bitcoin — or rather, monetary libertarians — emphasize that financial crises aren’t caused by money. Bitcoin is a return to fundamentals — a rectification. Why does the Fed base policy on unemployment rates and inflation indexes? Because their policies cause money to intervene too much in the economy and free market, creating dysfunction.

Now, returning to a more fundamental and original form of money is like detoxifying the market — painful but necessary. It’s not about creating a new form of regulation, but about decoupling money from economic manipulation.

935:So Bitcoin isn't trying to become a new tool for financial regulation, but rather a more effective store of value?

Hu Yilin:That’s not the full picture. Bitcoin respects the market. Money is a commodity, just like pork or real estate. Its influence is no different. OPEC can manipulate oil prices and use them geopolitically. But money is a very special commodity — it's the most neutral. That’s why it can serve as money. OPEC controls oil, so although oil has monetary attributes, it's not suitable as a base currency. Gold is better: it’s evenly distributed globally, Chinese and American gold are indistinguishable, unaffected by specific industries or institutions.

Today’s fiat is more like a monopolized commodity than a neutral currency. Bitcoin aims to return to being not only part of the commodity market, but the most neutral and unbiased commodity in circulation. It deserves to be better money.

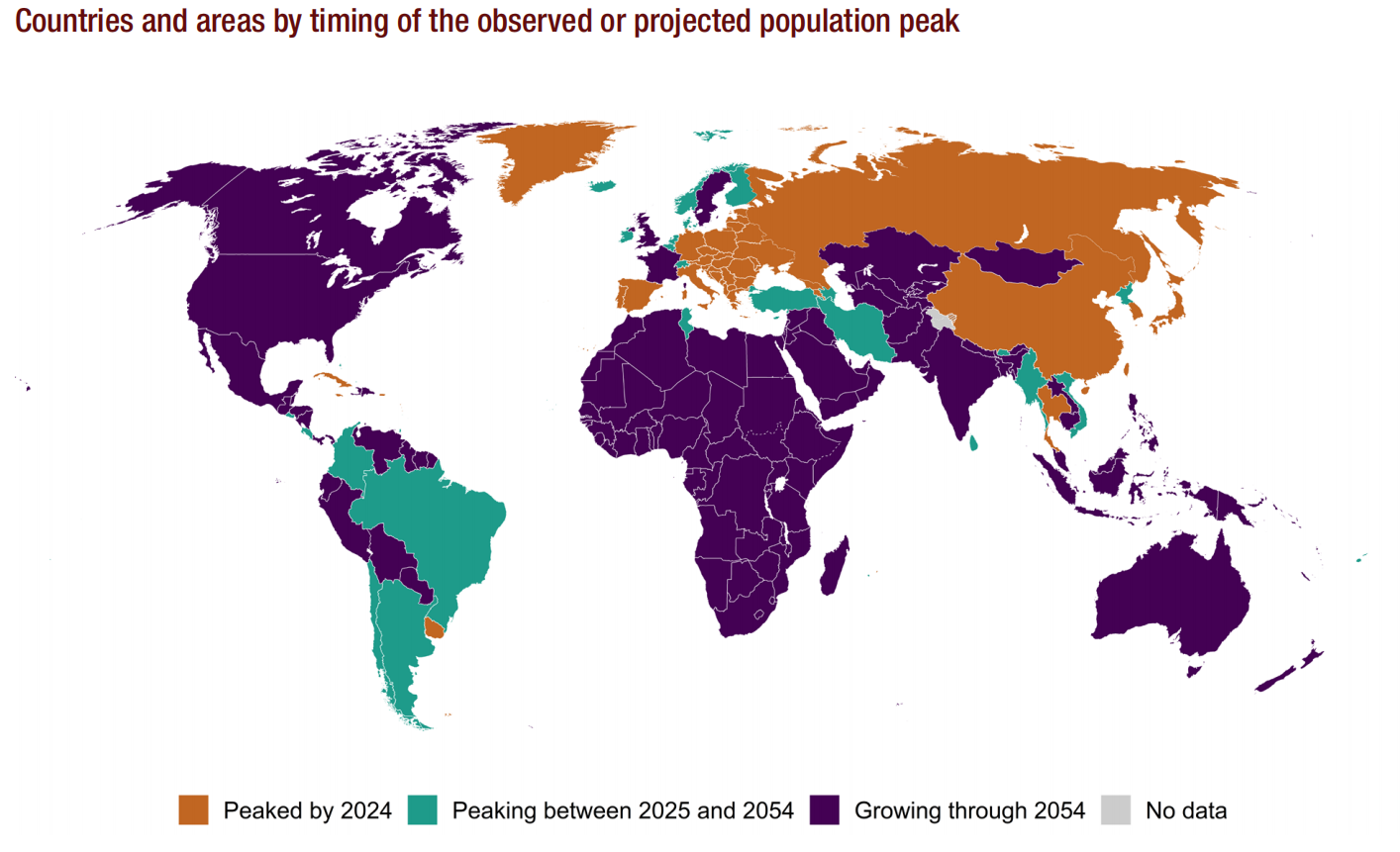

935:You mentioned our current system is one of growing populations and devaluing money. As a store-of-value currency, Bitcoin might usher in a model of declining population and appreciating currency. How does that work?

Hu Yilin:The fiat model doesn't suit a future with declining population. But even during population growth, store-of-value culture should exist.Chinese people understand this well — saving diligently for their children, or for old age. What makes humans unique is our foresight — planning ahead, preparing. We’ve always needed a way to store value: whether grain (“stockpile grain before proclaiming kingship”), or gold like a miser, or weapons for emergencies.In the industrial age, many traditional value-storage goods lost that function. Books used to be heirlooms. Now it’s often cheaper to buy new ones. Only real estate remains, and even that is hard to access in an unregulated, fair way.This is a problem in modern society.Humans inherently need to store value, but we’ve lost good methods.

One solution is financializing storage: real estate, stocks, securities, etc. Another is turning to gold and money.This isn’t a new model but a return. Bitcoin revives our instinct to store value. Technological optimism made people believe things would always improve, so what you save now might be obsolete in the future. But that belief is crumbling. The future may not be better — inequality is growing, crises abound.The pandemic reminded us: even rich families suffered. It wasn’t a money problem — they weren’t prepared.We thought everything would always be available, but in a crisis, suddenly we had nothing.This rising uncertainty brings us back to preemptive preparation. Money is just one storage method. It's a shift in mindset — from indifference to concern for the future.

Flytofu:But the crypto space, or Bitcoin ecosystem, feels very unstable.

Hu Yilin:Actually, Bitcoin is the most stable and conservative investment — because it doesn’t change.One comment from Powell can swing the total USD supply dramatically. Even over a decade, the dollar isn’t the same. But one Bitcoin is one Bitcoin — unchanged for eternity. Ontologically, it’s stable — a long-term bet on the future.Societal economic growth is driven by technology — and tech is arguably the only stable long-term growth force. Politics fluctuates, culture changes. As long as tech advances, total economic output rises, and a fixed-supply currency like Bitcoin appreciates.

Fiat supporters say hard-money systems can’t keep up with economic and transactional demand, leading to deflation. So they inflate fiat to match growth. Fiat is designed to depreciate.But Bitcoiners argue that logic is flawed. Currency appreciation doesn’t crash the economy — that’s the Austrian School view.We’ve never had a Bitcoin standard, so it’s untested. Belief in a Bitcoin-based world is still mostly a matter of faith.

Flytofu:Compared to gold, what’s Bitcoin’s advantage?

Hu Yilin:First, gold’s supply isn’t very stable — extraction tech and speed are unpredictable.Second, gold is inefficient — hard to carry, verify, and divide. In theory, it’s infinitely divisible, but in practice, you can’t use gold leaf for small transactions without verification. Because of these material limitations, gold tends to be stored centrally, and thus gold standards rely on paper as proxies. But redeeming paper for gold is hard — like when Germany tried to get its gold back from the U.S., it took massive national effort, diplomacy, even threats.This centralization makes trust fragile.

Bitcoin is more flexible — divisible. Yes, transactions have costs, and there's a practical limit to how small it can be used. Like gold, it will use proxies — Layer 2s, Lightning Network, etc. But Bitcoin’s redeemability is easier and decentralized. Bitcoin can have relatively centralized tokens for daily use, but you won’t face a scenario like storing gold in the Fed and being unable to get it back.

Flytofu:Do you think Bitcoin is essentially a store of value, a unit of account, or a payment method?

Hu Yilin:Money is both a store of value and a payment method — they aren’t contradictory. Bitcoin is money. People confuse medium and value. A ¥100 bill holds value, but it can also be represented by checks, plastic cards, or even digital Alipay accounts. The payment tools are cards, Alipay, etc., but they all carry the value denominated in yuan.

Similarly, Bitcoin is confusing because the word refers to many things: wallet software, protocol, blockchain, unit of account, ledger.It has many payment methods: main net, Lightning, sidechains, centralized exchanges, future stablecoins, etc. Bitcoin is the unit of account across these platforms — it’s not the payment method itself. The main net is too slow to serve as the only payment method. So I hope for a Bitcoin-standard world where all those platforms replace the RMB unit with BTC.

Flytofu:But people argue that Bitcoin’s fixed supply makes it unsuitable as currency.

Hu Yilin:After the gold standard collapsed, the U.S. blamed gold shortage — not greed — for monetary over issuance. But that’s just breaking trust. If no one can print more money, then “those with money fight, those without don’t” — peace may follow.

Flytofu:If we don’t overissue, doesn’t a Bitcoin unit represent more and more real-world value over time? Isn’t that unstable?

Hu Yilin:Technological progress is stability.In our era, the more tech in a product, the faster it depreciates. Phones lose value yearly. In contrast, traditional wealth-like property, land, energy — the assets of old money — appreciate. Tech goods always depreciate. This doesn’t hurt free markets — only affects low-tech traditional assets.The elites sell you a lie that currency depreciation helps you. But they thrive on debt. Future money is cheaper than past money, so the more debt, the richer they get. Pensions rely on future workers paying past debts — unfair, since the poor can’t borrow.They save pennies their whole lives, only to see it all devalue.

This model is collapsing under population decline — the Ponzi scheme can’t continue. Once 4 youths support 1 elder, now 1 youth supports 4 elders. The world used to inflate while money devalued. Now it’s falling apart. Even without Bitcoin, this system is unsustainable. Why should young people bail out past investments — housing, Moutai stockpiles? They refuse. We’re done being the exit liquidity. You old folks lived off passive income, but now young people work their whole lives with no children. So we reverse the game: declining population means appreciating money — Bitcoin fits this future.

Flytofu: But many fear Bitcoin is being “captured” by the U.S., especially with ETFs heavily influencing price.

Hu Yilin:It’s not that the U.S. has assimilated Bitcoin—it’s that Bitcoin has assimilated the U.S., because Bitcoin hasn’t changed; it’s the U.S. that has changed. For the U.S. to bring Bitcoin under control, it had to revise its legislation, but Bitcoin’s protocol and code didn’t update for Americans or make a special version for Trump. On the contrary, Bitcoin will increasingly influence the U.S. dollar. The U.S. is treating Bitcoin as a reservoir for the dollar, and we are moving in the direction of a Bitcoin standard.

Moreover, when it comes to buying Bitcoin, everyone is equal. Compared to ordinary people, the U.S. actually has a disadvantage in over-the-counter (OTC) transactions because the processes are more complex. In front of Bitcoin, everyone is equal—it’s just as easy (or difficult) to buy with 100 RMB as with 10,000 RMB.

The dollar is exported via lending, and those closest to the top 1% of society—the top of the pyramid—have much easier access to loans than ordinary people. Those closest to the faucet get water first: they borrow more easily, earn more easily, and let their capital appreciate faster through interest. But Bitcoin is equal—there’s no interest, and everyone buys at the same conditions. In fact, individuals might even have an advantage.

Flytofu:Nowadays, people also worry that central banks or large corporations will hoard Bitcoin and not release it for circulation. At the same time, block rewards keep halving, which means miners’ rewards and transaction fees will continually decrease. Eventually, there might be no incentive for miners to maintain the network. Do you share this concern?

Hu Yilin:If the Bitcoin standard doesn’t succeed, then yes, this risk exists. But if it does succeed, then this issue won’t be a problem. A large portion of daily transaction settlements is currently handled by centralized third-party platforms like Alipay. These platforms themselves also need to settle accounts—otherwise, the money they issue wouldn’t be "real."

A Bitcoin standard would disrupt the current financial order, but there would still be tiers in the new financial system. Instead of a central bank, the main net becomes the most reliable layer. Beneath it, there would still be branch platforms like the Lightning Network, payment channels, Alipay-like services, centralized exchanges, and so on. Most everyday transactions would take place in these layers. Even if ordinary users aren’t making purchases, they still need to withdraw Bitcoin from these platforms. Institutions will also have settlement needs between each other.

Back in 2017, people were debating that Bitcoin was becoming too congested and needed urgent scaling. Now the debate has flipped—Bitcoin seems too quiet. The whole Bitcoin market is still immature and unstable, so fluctuations are natural. Sometimes it's crowded, sometimes it's empty. A robust self-regulating market mechanism hasn’t yet formed; the entire ecosystem isn’t sound enough.

Big institutions may be hoarding Bitcoin, but does that mean there's no trading? The same goes for ordinary users.

Calling it a Bitcoin "standard" is the most accurate term. Under a Bitcoin standard, there can still be many powerful other tokens, securities, or projects. They might be more attention-grabbing, but Bitcoin serves as the backdrop behind them all. That’s what the Bitcoin standard means. It doesn’t mean Bitcoin is the most supreme or godlike thing—but it is the most foundational and stable.

The Many Faces of the Crypto World: Memecoins, Trump Coins, AI

Flytofu:When we talked last year, the Bitcoin ecosystem was still in its early stages. Now, a year later, do you feel a bit disappointed?

Hu Yelin:This whole space needs chaos. Back then, one big problem with Ethereum was that it was like a revolutionary who had just taken over a mountain stronghold and immediately started thinking about establishing a long-lasting dynasty and pushing for environmentalism. Ethereum switching to PoS was incredibly stupid—as if they thought they'd already become the leader of the world and should start worrying about the future and sustainability.

Bitcoin forked itself and fought it out. In the end, no one made a final call—it was all market-driven. If the market truly needs PoS, then let the fork happen when the time comes. But Vitalik has this sense of responsibility—he's a good person, and that’s exactly the problem. He’s like an enlightened monarch. But even a good monarch is still a monarch. This space is still in the era of Chen Sheng and Wu Guang (early Chinese rebel leaders). Maybe there are some Liu Bangs and Xiang Yus (founders of new dynasties) emerging, but it’s still a time of chaos—not yet time to build a hundred-year legacy. Those long-term foundations must come from the battlefield of the market, not top-down decisions made impulsively.

Looking at Ethereum’s actions, I feel like it’s not going to work. Right now, the logic of the crypto world—or rather, the entire ecosystem and its game—hasn’t truly matured. It still needs chaos. Bitcoin’s ecosystem is also part of that chaos.

That said, Solana does fit the fast-in-fast-out enthusiasm of the market. Lately, I’ve actually been more supportive of the Solana ecosystem. Its existence is reasonable—we must respect the market. Even though I personally like the Bitcoin ecosystem, if I bet wrong, I need to admit that. People's interest and energy are still focused on these things. Meme coins also have meaning, in a sense.

Flytofu:Where do you think the value or legitimacy of meme coins lies?

Hu Yelin:Meme coins are cyber protests. Revolutions are inherently chaotic and violent. During revolutionary marches, many people act irrationally—looting, smashing, and destroying machinery. Western history is full of such episodes. Modern capitalism looks stable now—democracy, common law, all seemingly solid—but if you look back to the transformative periods, two forces were always at play.One was the elitist group: Rousseau, Hume, Montesquieu—they had utopian visions, practical suggestions, and made real efforts. They were the idealists and builders.The other was the force of the masses—irrational and riotous. A new idea emerges, they riot, loot—even if they don’t fully understand what they’re pursuing, and have no long-term goals. Both forces are necessary to overthrow the old world. Elites without a bottom-up movement don’t work. Grassroots action without elite guidance also fails. Even if they don’t respect each other, at the very least, they need to acknowledge each other’s existence.

935:This technology was supposed to be a tool for the future—a way to resist the overly technocratic, overly quantifying, science-centered features of modernity. But the philosophy behind our use of it seems to be returning to modernity—for example, “code is law,” putting all trust in math and code.

People say everyone has equal access to buy Bitcoin, but how can we be sure that social power structures won’t eventually seep into Bitcoin? Will power and hierarchy reshape the protocols?

Hu Yelin:The problem with modernity isn’t that science is wrong—it’s that it’s too right. It erases other imprecise but important values. Reflecting on modernity doesn’t mean rejecting science—we still believe in it. I often use photography as an example. A photo of you is accurate and conveys your likeness. But it’s not you. It’s just a medium. You contain far more dynamic and rich information than a photo.We trust the accuracy of technology—but it shouldn't be the only way to understand the world.

In Bitcoin, we do rely on technology and math. But ultimately, what matters is people—the social trust in shared expectations. You open a butcher shop based on the assumption that people still eat pork. That’s not science or math—it’s a shared human understanding. Can Bitcoin's supply limit be raised? Can it be shut down? Yes—if people collectively agree. Its stability isn’t absolute in a mathematical sense, but in a socially expected sense.

Flytofu:What do you think of Trump launching his own coin?

Hu Yelin:Trump really knows how to play. A veteran businessman and rogue with nothing to lose.

For those who believe in liberalism, this might actually be a good thing. We all admire Hayek’s Denationalization of Money, which advocates for private and corporate issuance of currencies. In a true market economy, money is just another commodity. It shouldn't be monopolized by anyone. If anyone can issue currency, then of course Trump can too.

This is a powerful example—it tells everyone that anyone can do it. It's a return to liberal principles. In the short term, it will affect the market. Everyone will come to fleece the retail investors. Once the low-hanging fruit is picked clean, the market might dip. But in the long run, it represents progress for liberalism. Using such a low-brow method to issue coins demystifies the act of minting money. That’s a kind of ideological liberation.

935: But only if these coins are actually used in transactions can they be considered true “denationalized currencies” in Hayek’s sense—like in the free banking era. Right now, most “coins” seem more like disposable consumer goods.

Hu Yelin:Circulation comes in different scales and contexts. It's like influencer economies now—fans send tokens to streamers for rankings. They might rank high, but it doesn’t mean they’re making much money. Currency is still a commodity. Some commodities have long-term circulation, others are short-lived. Some are hot for a few days, some for a few years. Even gold standards and the U.S. dollar were only dominant for 30–50 years. Celebrity coins, influencer coins—they’re all part of the ephemeral influencer economy.

Our past imagination was too narrow. Back then, there weren't so many fancy uses for currency or tokens. Now, issuing coins isn't limited to opening a bank. Influencers can issue tokens. A coffee shop’s coupon is also a kind of token. The blockchain just makes it more transparent and tradable. Originally, your coupon only worked at that shop. Now, if there's a market to trade it, it becomes something broader than just a unit of account—it’s a token in the wider sense. That fits with the times.

Many people think the times are corrupted—that it’s all gone wrong. But today is the age of entertainment. The internet is irrational by nature. Finance has come down from its sacred pedestal. Crypto traders are no different from Wall Street financiers. This is decentralized, transparent finance. Everything is tradable and for sale. If something can’t be monetized or doesn’t yield returns, how does it matter to individuals? Only things that can be financialized are truly under your personal control. Influencer economies are emotional economies. Emotions are invisible and intangible—but tokens turn emotion into something tradeable.

Flytofu:What’s the significance of crypto to AI, and vice versa?

Hu Yelin:Today’s AI is being framed in this elite, liberal “AI safety” narrative—like it’s dangerous and must be tightly controlled. They want to carefully embed their values into it so it doesn't go rogue. But that’s wishful thinking—and arrogant. Why should your small group of people represent humanity’s values? You can't even agree among yourselves! And even if you could—it shouldn’t be that way. The future must be open—and it needs a financial model to support that openness. AI burns money but also makes money. That flow of funds needs managing.I’m not against some structured form of AI governance. We need small groups, communities, or institutions to train our own AIs. When we can train our own AI, we also need ways to finance, invest, and profit from it. We shouldn’t be stuck in an overly globalized, capital-driven model—because in that model, the strong only get stronger, and it’s all centralized again.

The only thing that can challenge the big players is decentralization and open source. But open source has a problem: it doesn’t make money. Like the Linux era—developers did it for love, powered by hacker spirit.But AI’s cost and returns are both huge. It brings tremendous social value. So we need decentralized financial systems to support open-source AI. Blockchain’s open contract systems can create relatively independent governance models.

Flytofu:This is starting to sound like science fiction.

Hu Yelin:Even more sci-fi: what if AI agents become sentient? What currency would they use? AI needs energy and will produce things that need to be traded—would they use U.S. dollars? Controlled by the Fed? Probably not. They’d use crypto—Bitcoin or something like it—as a basic currency.

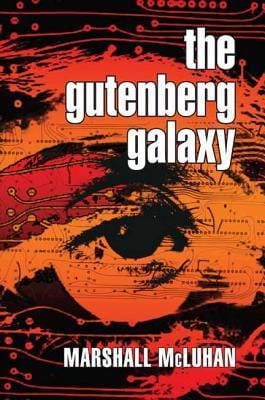

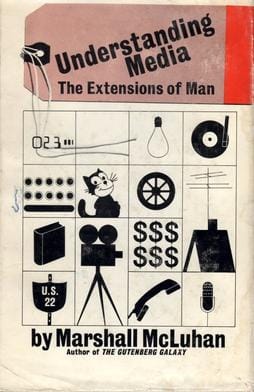

But more realistically, we need diversity in AI training. Both left and right agree the world needs pluralism and to resist globalization. The internet’s problem is how to maintain diversity in a world where information flows too freely. McLuhan predicted in the ’70s that the electronic age would turn the world into a village—which he thought was terrifying. Everyone crowding into one village would create noise, chaos, and erase boundaries between people. Those original boundaries protected cultural diversity. But the internet eroded geography. Urbanization made big cities look the same. Local dialects fade. Universalism that flattens everything is wrong. We need to return to a pluralistic world. But it’s hard to fix pluralism, so the Western left ended up using race as a proxy—because culture and geography have been erased, all that’s left is skin color. But that’s a narrow way to distinguish people—like classifying animals.

The real solution is to return to small communities and shared living. In big markets, we need “enclosed gardens” with boundaries. Currency and economic systems are also boundaries. In the internet age, the nation-state narrative is outdated. The future must be newly imagined communities, and their boundaries may be defined by blockchain. I used to dislike it—every DAO and community felt the need to issue a token. But issuing a token

does create a buffer—a right to self-determination and a small internal economy. Web2’s internet was totally flat and boundaryless. Now we’re using these methods to return to a relatively bounded ecology.

In tech history, when something spreads too quickly, it risks replacing adjacent technologies. Like ancient Rome invented glassware, but China used ceramics. Early on, they were isolated. But when they connected, ceramics outcompeted glass. If they had connected earlier, maybe glass tech would’ve died out. Then we wouldn't have telescopes or microscopes. Boundaries allowed each to develop their own tech trees, and then later merge. AI is the same. If we only pursue productivity, we’ll end up in a Matthew Effect loop—efficiency homogenizes everything. But if we let different communities train their own AIs based on their preferences, the results could be far richer.

Flytofu:

In your book Introduction to the Philosophy of Technology, you wrote: “We cannot expect to control the overall trajectory of technological development through individual effort. However, individuals have always had room to exert influence when facing specific technologies.” From the perspective of an individual, how can we—each of us seemingly insignificant—help influence the direction in which crypto is heading?

Hu Yilin:

Hoarding coins is the most direct form of influence. What you hoard is what you support. I hoard Bitcoin, so I support Bitcoin. If you hoard U.S. dollars, you're supporting the dollar. Your actions should align with your ideals. Second, try out new technologies—experience plugin wallets, NFTs, and the new forms of social organization built on the blockchain, including living as a digital nomad. Everything you do contains your political stance. When a programmer develops a small, specific technical feature, they are also expressing their political beliefs.

Modern society has created a kind of numbness—people no longer think about the consequences of what they do. They simply follow orders from above, fulfill their assigned duties, even to the point of producing the rope that will hang them. So, to break free from this modernity, the first step is self-awareness: to reflect on the ideals and values behind every action. Why are you doing this thing? What does it provide? Who benefits from it? What kind of impact could it have on society? Everyone is worthy of this kind of reflection—that is what freedom truly means.

Flytofu:

In your book, you also wrote: “Human freedom lies not only in being able to choose between rice and noodles, but in the capacity for constant self-reflection and transcendence.” That line really encouraged me.

Uncommons

Reporter: Flytofu&935

Translator: 935

Edit:0614

The sources of the images in the text have been identified.

Who we are 👇

Uncommons

区块链世界内一隅公共空间,一群公共物品建设者,在此碰撞加密人文思想。其前身为 GreenPill 中文社区。

Twitter: x.com/Un__commons

Newsletter: blog.uncommons.cc/

Join us: t.me/theuncommons

Discussion