Crypto Flight Vol.10 | Reflecting on Technology and the Commons in Times of Historical Transition: Interview with Michel Bauwens

“Why did he refuse the Bitcoin offered by Satoshi Nakamoto?”

Michel’s life story

Correspondence with Satoshi Nakamoto

Dangerous technologies: projections of transcendence

The technical construction of the real world

Externality Crisis: The Cunning of Capitalism

Rebuilding an unbalanced society

System scalability: creating surplus value

💡Reporter's note

Our encounter with Michel in Chiang Mai was nothing short of exhilarating. Interviewing him filled us with profound excitement, for he is a living relic of an extraordinary era—a tumultuous age defined by the Cold War's icy standoffs, the feverish space race, the zenith of hippie movements and counterculture, waves of social upheavals, anti-colonial struggles, and the rise of avant-garde art. These collective experiences served as a spiritual prelude to the technological revolutions to come. We couldn’t help but wonder: what indelible imprints has such an era etched upon those who lived through it?

Through our conversation, we delved into Michel’s past and his acute observations on contemporary societal challenges, particularly his vision for establishing Global Commons. His analytical framework—spanning macro-historical perspectives, philosophical inquiry, and ecological consciousness—revealed a unique amalgamation of idealism, Christian theology, and Marxist critique. His uncompromising assertion, “ we are not human yet, let alone posthuman,” might strike some as rigid orthodoxy. Yet beneath this severity, we discerned the unwavering conviction of a seasoned idealist and veteran advocate of digital revolution, whose faith in humanity and pursuit of beauty radiates undimmed.

In many technology-dominated circles, such direct engagement with humanistic concerns and earnest yearning for truth, kindness, and beauty has become a rare artifact. Michel’s worldview, forged in the crucible of that transformative epoch, stands as both a rebuke and an inspiration—a reminder of what we risk discarding in our headlong rush toward algorithmic futures.

About

Michel Bauwens

Theorist in the emerging field of peer-to-peer (P2P)

Writer and conference speaker of technology, culture and business innovation

Founder of P2P Foundation

935

Mind in the 20th century, body in the 21st century, mind in the 22nd century crypto movement and philosophy of technology researcher.

7k

Technology and media researcher. Focuses on monetary history and the cryptocurrency industry, cypherpunk culture.

Michel’s life story

935: We know you are from the 60s and 70s. Looking back at that era from today, many of the influences we see now actually began during that time. For example, The Whole Earth Catalog is a product of that era. Did you have any interaction with Stewart Brand and his Whole Earth Catalog network? What early experiences sparked your interest in the social changes that information technology could bring, and did they lead to the creation of P2P Foundation and P2P Wiki you started?

Michel: I'm from the same generation. I used to subscribe to the Whole Earth catalogue and everything. I met Stewart Brand and Howard Rheingold.

I'm a working-class kid. My mother was almost illiterate. People forget that even in the 60s, how many poor people there were still in Europe. So I was not happy as a child because I was taken away at 18 months from my parents. I had asthmatic bronchitis and was put in sanatoriums. I remember having to eat my vomit, and being in a glass cage...... So I was kind of a traumatized child. So my first actual reaction was to be a Marxist. I was with the Vietcong when I was ten. I was already watching the news and everything. I was premature.

After seven years of activism, I thought, this is not working, the world is not moving in that direction. In the 80s, it was actually counter-revolutionary, you know, Reagan, Thatcher... And I thought, okay, if I'm unhappy and if I cannot change the world, then the only solution is I have to change myself. So then I took a journey of healing. First, I lived in a sex commune in my 20s. Wilhelm Reich who wrote The Sexual Revolution, we should check him out, really interesting guy. Basically, we thought that if people are unhappy that is because we repress our sexuality. Anyway, I did all the California stuff, rebirthing, seminars, primal scream, I did it all. And then I went to the East, I did a lot of meditation and stuff, and I ended up with Osho, which is Indian. So if you watch, you have to watch this. It's super good, The wild wild Country on Netflix. I was there the year before it collapsed. That's what the documentary is about. And so then I went a bit to the West, so I did you know, I studied alchemy. I was a Templar, Rosicrucian, a mason, trying out different things.

Then by the time I was 35, I calmed down and I thought, now I have to be creative. I have all these tools and I no longer thought of myself as being more fucked up than anybody else, and that's when I started the internet period. In the 90s, I was really one of the first ones in Belgium to get how the internet would change everything. I think between 1990 and 1993. Not very early, but still quite early. This was Gopher, FTP... stuff that now is all hidden behind the web. But I really understood and I still think this is going to change everything. The real time connection of human brains outside of the control of state and market. We never had that. So the scale free collaboration was my idea.

I did two startups in the 90s. The first one was very successful. I sold it and I have a big house because of this. The second one was crashed in 2000. And I had some kind of burnout, because the startup. I don't recommend it. It's deadly. You have to work so hard and it's very risky.

I ended up being a strategy manager for this huge telecom company. And I saw so much corruption around me that I thought, I can't do this. I have to cheat with accounting, add zeros... So I thought, actually, the thought came up that the accounting of big capitalist enterprises is not more trustworthy than the accounting in the Soviet Union. It's completely fake. And I thought everything is getting worse. Like more pollution... Especially at that level of enterprise, everybody is divorced, there's a lot of cocaine. I was the only one not taking drugs. And all my colleagues were going to prostitutes and stuff. I didn't feel at home there.

That's when I started thinking should I go back to Marxism? And I read Empire from Antonio Negri. Went back to postmodernism, I started reading Foucault and also after 95, I started seeing the network form. The anti-globalization movement, the Zapatistas. If you think about the Zapatistas, they were like a small indigenous army. They could have been wiped out in a month by the Mexican army. But they couldn't do it because they had solidarity mechanisms, the whole world. So the reputation cost (to wipe them out) was too high. So this was after 95. You could really see the network form becoming very efficient and open source and open design.

And I thought this is it. This is what I have to do. So I also took a two years sabbatical, 2000-2002, to study transitional periods in human history. That's where I came up with my theory of seed forms. So I was seeing my theory and I said, okay, this is what I have to do. I have to monitor the seed forms and see where this is going.

The difference with Marxism is, (in Marxism), you want to take power and then you will change everything. But societies change because for a very long period people are reinventing societal logics. And then when they're strong enough, you have a revolution. Only then, but not before. And the revolution can take many different forms. And actually it's only necessary when the system is so stuck that you need a revolution to change it. You can change in many different ways. If you look at history, the Russian and the French Revolution are outliers. They're not the norm. But Marx took them as the norm.

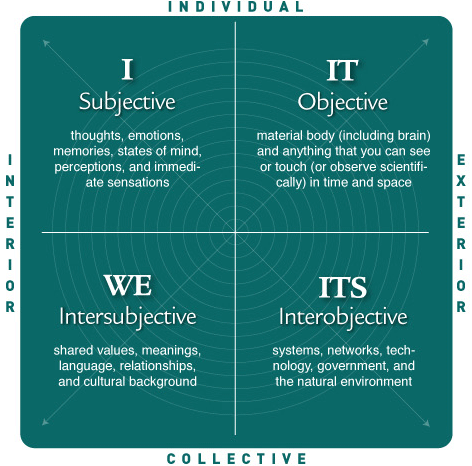

I was very influenced by Ken Wilber and integrative theory, which is basically a kind of a blend of historical materialism and historical idealism --- We can't really say what's primary, so let's just take everything, subjective, objective, individual collective……so if you want to change you have to look at the four quadrants and ideally design change. You try to make sure everything changes at the same time. Because if you only do one thing, it won't work.

I took two years sabbatical, did another two years studying Thai history and the Thai culture studies. And then in 2005, I started the wiki and then the blog, and people started inviting me, and gradually everything went very well until 2018 when I got cancelled. That was pretty hard for me because I lost everything. I was working with ten people, I lost all my funding, I got blacklisted. I used to be invited in cultural festivals and everything. But instead of getting depressed about it, I just said, let's use my time to go back to transitions but deeper, longer. And I started reading all the macro historians. It's only last year that I came back to the public.

And of course, I don't want to restart, herding cats, organizing. Very tiring. Especially peer to peer. It's how do you get people to move in the same direction. It's very difficult. So I leave it to you guys, to the young people.

Correspondence with Satoshi Nakamoto

7k: Can you say something about your interaction with Satoshi?

Michel: It was not that intense, Satoshi wrote me a few times, one of the emails was about explaining why he was publishing his white paper on our site. And offering me a few bitcoins. Unfortunately I didn't answer that proposal. And then he wrote me again when the Japanese guy was out, Satoshi said I'm not that person. And the third time he said I'm going to write to you, but he didn't. But I was the first person to tweet about Bitcoin apparently.

I was not excited about, like the energy requirements that were embedded in it and stuff. But I was excited that it was the first globally scalable, socially-sovereign currency that was not created by a firm, nor by the state.

Then the ledger, this is the first time we have a universal ledger. So we moved from closed accounting systems to open ecosystems for accounting where we can embed, thermodynamic flows and contributory flows. So now we can see ‘curren-sees’. I saw this as a post-capitalist invention. It doesn't mean anti-capitalist. It means transcend and include. It means giving it a place, but embedding it in something that has a higher complexity and that can constrain it. And I think this is the right way. We've been anti-capitalist for 200 years. I don't think it was very successful.

7k: And there's also research about how Bitcoin is cooperating with capitalist. It's more like an alternative way of investment.

Michel: But I think it can be both. This is a historic analogy: at the end of the Roman Empire, Rome fell, but it actually still existed as a political system. Even though it was managed by the Germanic warlords, they were (just) the military occupiers, the system was still functioning. So if you were part of the Roman elite, you could no longer go in the army. You could only send your children to the church, which was the state in a way. So it made a lot of sense for the Roman elites to fund the Christian church. They financed monasteries because it's in Latin. Your son and your daughter can be the abbots and abbesses, and you can retire there.

So in a way, I see something similar happening to Bitcoin and the blockchain where people with capital were also seeing the bad signs, looking for a way out. So it's an exit strategy and it's an arbitrage between nation states. And it has been democratized, this is also important. It's not just like trans financial capital which already has existed since the 1980s. And then the coding class which is also the elite, highly educated, usually well paid, can coordinate labor to social signaling because you have open source and community. So you can finance your own commons.

But what is missing is the connection with productive reality. And I think that has to change. My own dream is to connect the forces of Web3, which create scaling capacity for capital, with the forces of local resilience. That's the cosmo-logical logic that I try to push. Those people don't know Web3 and maybe even don't like it. And these people, a lot of them are just like profiteers, trying to have a good life while the world is burning. But I think there's enough good people here and smart people there to connect.

The only way to inflate the power of the commons is that way. We need productive inter civic commons institutions. Today to be a citizen and part of a network, you are productive. In the old view, the citizen is what you do after you finish working. It's non-profit. Non-governmental. It's like derivative. And I think what we are seeing is every citizen, through his engagement in these productive networks is productive as a citizen. In a commodity labor, you only give your labor. It has no meaning. It can have meaning if you're lucky, if you can sell it to the right project. But that's like one in 5 persons. But in in the contributory economy you are freely associating your skills and passion. So you're a full person.

The other thing I say is that the new organizational form is organized networks with commons. That's what we're creating. We're creating a meta-container which can transcend and include markets, public authorities, voluntary work, permissionless contributions in one higher level of coordination. But in order to be the next thing, we need power. So it means we need property. We need to start buying up stuff. We need to buy land, housing, cooperatives, community land trusts. We should be buying stuff and doing it trans-locally.

And then you can also arbitrage, if you have trouble in one place, you can direct forces to it. This is where I think if you're progressive, you have to be realistic. Because this is something that you do all the time in Web3, imagine the world. But you also have to think, well okay, how do I get there? And it's not just like doing stuff because you will have enemies.

Dangerous technologies: projections of transcendence

7k: There’re many questions here. But I think the most interesting thing is, many people say there’re similarities nowadays with the early history of the internet. Also in the recent article you wrote, you described the Pop-up city as the ‘Civium ’. How do you see the similarities of this trend of internet movement with the previous one?

Michel: So I think it's better in a way, because the first generation was very idealistic. Now people are much more cynical and careful. They're trying to recreate the lost opportunity of the early internet, but with a lot more care and protective mechanisms.

As an old lefty, I have a hard time with libertarianism personally, especially ‘an-cap’, Anarcho-capitalist libertarianism. Because that's what mostly the 1980s is about. But a lot of Web3 people believe in this. Which is really another iteration of the market will solve everything. And I don't believe that at all. I don't believe I could solve everything. I think they're efficient for certain things.

So the common point between left and right anarchism is the denial of the fields. It's only people with relations, maybe they make an agreement, but there's no society. And I think that doesn't work. Society is there first, individuals come later. They don't realize how much of their thinking is determined by the kind of society they live in. And they just push the idea of society away. But I think society needs to be organized, that's what civilization is. Civilization is basic decisions about how collective life should be organized. And then you educate people that way and your brain is cultural. It doesn't come out of nothing because you're a free individual. And of course you can go to Collectivists and you can go to individualist, but the challenge is finding the right balance. In a way that, what we're trying to do now is finding the right kind of community for people as they are today. Not always easy to find the right way to do that.

7k: I think most of your work is based on the emerge of internet and the invention of blockchain and other technology innovations, would they be able to lead us towards the direction we talk about?

Michel: There are two main scenarios regarding how technological innovation benefits us. Fundamentally, the world is organized through matter and energy, but the way we manage this organization is through information technology. In societies without writing, such as hunter-gatherer communities, knowledge transmission is limited. Learning occurs directly from parents to children, like fathers teach sons, and mothers teach daughters. This keeps societal structures relatively static and in balance with the environment, often remaining nomadic. Once we have writing, then you can transmit high level technical knowledge to the next generation.

So when you reach a crisis, you can fall down to a lower level of complexity, or you can go higher. An example of lower would be the Roman Empire, where everything goes back to the rural cities disappear. Roads are no longer maintained. You know, the, the feudal era. It's not all bad, but it's a very low level of technology. But after the 15th century, we had a similar crisis in Europe with the Reformation, and we lost one third of the population through fighting. And then we went to capital state nation. We went to a higher level of complexity, but because we had print.

So that's why I think the internet is important. It allows this kind of very detailed peer to peer transmissions, self-organization at scale. Commoning and gifting at scale. So I think if you want to maintain the benefits of this technology, longer life, (treat all) kinds of diseases, or mastered the level of pain that people had even 70 years ago. if you want to keep the benefits of modernity, we need to use the internet, but we don't have to use it in the same way we're using it now. Because again, think about capitalism, it's about our lower drives in order to make money. It's all about TikTok entertainment, Instagram, you know, and just keep us busy with unimportant stuff.

935: You mentioned that we don't necessarily have to use the internet in its current way. What would be a better way to use these digital technologies?

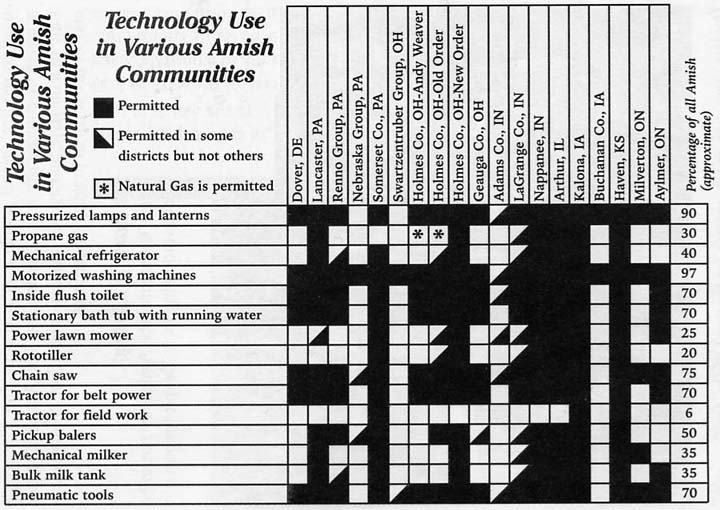

Michel: First of all, we don't have to use technology in the way that is commonly accepted by mainstream society. For example, religious communities like the Bruderhof, also known as Hutterites, they are tackling technology in different ways. In the communities, everyone has their own apartment, but they also come together for shared evening meals. Clothing is collectively owned through a “cloth library,” and internet access is limited to a communal library rather than individual devices. I’m not necessarily advocating for this lifestyle, but it illustrates that there are many ways to engage with technology beyond the default assumptions of modern society.

We always regard technology as a force of nature that we have to obey. That is not true. Throughout history, civilizations have consciously chosen to regulate or reject certain technologies. Examples include China at some point, Japan in the 16th century,and the Amish, who have successfully maintained a 17th-century technological level while living healthy and sustainable lives. These examples remind us that we can take a more deliberate approach to technology, shaping it to serve our values rather than allowing it to dictate our lives.

We must be cautious, as many technologies carry unconscious values behind their use, with various ideologies embedded within them. I think there's value driven design or value sensitive design. I did a documentary about transhumanism in the late 90s, It's called TechnoCalyps: the Metaphysics of Technology and the End of Man. And my conclusion back then was that transhumanism was an unconscious religion. We stopped believing in the 16th century, the elites in Europe. So we started secularizing. Basically what we did was collapse everything we believed was transcendent into the horizontal plane.

There's somebody I met, Richard Thompson, who had made a map, the 64 Powers of Yoga, which people believe you can obtain through yoga. And what technology is doing was the same -- technology is really trying to manifest in material reality everything humanity was trying to achieve in spiritual reality. But they're not conscious of it. And that's dangerous.

So they have these very deep religious drives. Omniscience, omnipotence, all the divine characteristics are now actually projected into technology. And that makes it very dangerous. So I'm personally totally opposed to transhumanism. I think we're not even human yet. I don't think we should be post-human, transhuman.

The technical construction of the real world

Michel: We can think of technology through the lens of current issues.

For example, I think we have an issue of integrative capacity. I'm not sure about this, but I think things may turn out very ugly in the future, in terms of the disruption of supply chains, like a big war between China and the US could kill a billion people when supply chains are disrupted. Because our food is no longer coming from the local, we are super dependent on the whole world functioning smoothly. When that stops working. You can't just say from one day to another that oh now we grow locally. It takes decades. Not to say that now we have droughts. We have floodings. We have many things to think about. So in a way we have to shift from efficiency thinking to resilience thinking.

There's a Belgian guy called Bernoulli and he has an article about this. You can actually calculate this. When you become more efficient in the beginning, resilience also grows. But there's a point where you become more efficient and resilience actually goes down.

Because nature is super abundant. You have a million sperm to make one baby. So there's an overflow. And efficiency like in the neoliberal supply chain, there's no fat, no stocks at all. So the slightest grain of sand... just the system is very fragile, right? So we're going to have to shift to resilience.

There's this book. I haven't read it, but I think it's an interesting idea, Half earth socialism. Because starting in 2050, we have the exponential decrease of the human population. Imagine that one young person with eight old people eventually. So first it degrows slowly, but then it starts to excarte. And especially what's happening right now, which is almost like a refusal of young generations to make any children. It's very strong right now. It fell by 20% in ten years. So you know, the idea is to re-concentrate human beings and have the planet, and then give the other half back to nature. I don't know, it's an interesting way of thinking about it. Because we won't need that much. So I think this is going to be the priority.

I used to think a lot about spirituality, what kind of spirituality should we have. Are we going back to a new kind of religion? I don't know, but I think what's absolutely sure is we are going to have to re-educate people to life. Like are we hurting the capacity of the planet to reproduce life? And so I think the next civilization will have to revere life, regenerate, protect, preserve, rewild. There’re all these kinds of ideas.

And in that sense, we think technology is alienating us, hyper-mediating us. There's a lot of things that we will need to rethink. And maybe we will exaggerate in the other sense. Because if you look at history is big swings, big bifurcations. It's not like progress as we used to believe, when the Christians came to power after the Roman Empire, it's totally ascetic. They're not interested in technology at all. They want to live in accordance to their divine ideas. And I think the same happened in China with Buddhism and Taoism. In different moments in Chinese history, you can recognize that people actually completely went the other way. And then, of course, they create new problems because they exaggerate in the other way.

So I think the best way actually is to be integrative, is to start thinking in terms of balance. I don't know if it will succeed, but I think that's how we should be thinking about and how do we educate our children. Personally, I would like to see where first you do farming as a child. You learn about life, but how do you grow things? How do you care for animals? Then you move to industry crafts. How do I make things? And then you move to thinking. That's not what we're doing. Now if you send a child to school, he/she will never want to be a farmer. You abstract everything. And you deform people. Which was fine when, the elites were like 20% of the population, you can say, yeah, let's have 20% of population be intellectual. But when you do it for everyone, it becomes a real problem. So I don't think we should think about the internet as just continuing what we do now. I think we should think in terms like the Amish. They lived 17th century lifestyle in the US, Lancaster County. They use no electricity. They still have horse and buggy. But they're doing very well. They have the highest agricultural productivity in the US using old techniques. They make more food than agribusiness per person.

935: How do you think of Modernization? Do you think it might be a trap? Modernization is usually a product of Western narrative in my opinion. It claims modernization as an inevitable stage for every culture to evolve from the primitive. But is there a universal approach for culture evolution?

Michel: Do you know Wallerstein and the world system analysis? There are ‘core country’ and ‘periphery country’. The important thing in the theory, which I believe, is that the global determines the local. What you can do locally is determined by the global system in which you are part of. So, you're not totally free to do whatever you want. You're constrained by the forces. You are living in the environment.

There is another theory which you could use called ‘multilevel selection theory’. Basically, it says human beings evolve collectively and not individually. A strong person in a weak group has less chance to survive than a weak person in a strong group. We've always been competing between tribes, groups and nations. So, what that means is that constraints your freedom.

Because if you have one system that has better weapons, better forms of organization, better ways to mobilize their resources, they're going to defeat you. So that means eventually that you can read history as always following the victor. Let's say Egypt and Mesopotamia. It's only one system. Because if Egypt would get stronger and Mesopotamia don't do the same, then Egypt would invade them and vice versa. So as soon as you're in a system, you co-evolve.

935: But could this turn into something morbid? You are forced to evolve and follow. Even when that evolution might not be the best way. For example, in Chinese we have a word to describe this. It's called involution. Will this kind of phenomena also happen between country interactions?

Michel: I think this phenomenon is more grounded between countries. I'm reading a book, it's called The Shield of Achilles Filipovic, And it's a history of the state from Europe after the 16th century. He talks about princely states, Kingsley States, Nations states, and then market states.

But here's the thing. Napoleon comes on the scene after the French Revolution, and he's the first one to give guns to everybody, to the whole population of France to gets arms. And so he can come to the battlefield with a million people. On the other side, the English conservative kings, they only have 300,000 people. So, Napoleon is winning in terms of numbers of troops. At that moment, English has no choice. if you want to avoid being invaded by Napoleon, New England has to think, oh, God, now, how do we do it? They would say we should also have a million people.

When you have a country that is better, that becomes dominant, and everybody else must copy until they're the same level, and then somebody else will get better. All countries have a kind of almost of obligation to evolve, even in ways that may not be good ways. But it's being dominated. I think that's a very strong driver.

And this is going to be the difficulty today, how can we get out of this kind of competition? Sometimes it can end up something as negative as the nuclear weapons competitions, everything is going worse under this mode of competition. Normally speaking, every hundred years there's hegemonic war. 16th century Europe comes on the scene, the Portuguese, the Dutch, Britain for Twice, and then United States. Each time you have a war that puts a dominant power. World War Two brought America as the hegemon, the UK becomes marginal.

One of the theories, of course, is that now China might be the next hegemon. And that would normally cause a war. What's called the two leaders trap is that the dominant hegemon doesn't want to give up his power, and he's obliged to go to war like Athens did with Sparta, but then both weakened each other and then Macedonia came in. Anyway.

But the question is how we evolve to a world system that obviates the need for this kind of hegemonic war. We've never done it. We've never done it. That is the most pessimistic. So normally what happens is big reforms, including the world system reforms, they come after war. because the people realize the cost of the war was just so tremendous that we must avoid this all costs in the future. So then we reorganize the world order. But after four generations, people forget why they did it.

Externality Crisis: The Cunning of Capitalism

7k: Do you believe digital technology may help us to address externalities? I am hesitating to say that technology always helps. Because, for example, it’s impossible to rely on a supercomputer to measure and account for every form of contribution. So, how exactly can digital technology increase our capability to refine our current methodology?

Michel: That's basically what we're now doing with crypto and the software communities. About 5 to 10 years ago, I participated in a study called P2P Value, which focused on 300 peer production communities before crypto emerged. These communities operated on principles of open design, shared knowledge, and free software. At that time, 75% of them had already developed solutions for contributory work, you always have people to do tasks that are essential for the whole network but maybe undervalued by the market. This concept has since evolved into what we now call public goods in the crypto world. In many circumstances, crypto is delivering public goods, it has addressed the issue of collective action within post peer production networks.

However, I do need to point out that most of the objects that Cryptos creates are commons only to a certain extent. I don't think Bitcoin is necessarily the better option than capitalism. 12 people own like 70% of bitcoin. So, it is still about a few rich people who have the most commodity power.

But I think it is also important to see how things are moving in the direction. I believe crypto is moving in the right direction. Let's say if you're a leftist, and you believe that human beings are fundamentally good, it is the bad institution that doesn’t allow human to be good. I no longer believe that. I believe human nature is more complex, people are a mix of good and self-serving instincts. The key is finding ways to neutralize humanity’s more destructive tendencies. Paradoxically, Bitcoin has succeeded in part because it accounts for human gregariousness—our social instincts, including selfishness. But 95% of complementary currencies failed, because they only appeal to idealized notions of human goodness. Successful systems channel these "animal spirits" of selfish behavior into structures with higher ethical purposes.

This is, in essence, what civilization has always aimed to do. It cultivates civilization through social disciplines and training. Just like warriors are trained to follow the military discipline, otherwise warriors also have gregarious instinct to rape and pillage. Crypto, in its own way, are balancing human instincts and building a system that serves broader societal goals, which I believe is the right direction.

935: Long times ago, I used to feel that the 21st century was spiritually and culturally regressing compared to the 20th century. For instance, despite the two world wars, the last century was marked by remarkable scientific discoveries, profound philosophical thought, and high-quality artistic creation. Even in entertainment—movies, music, TV shows, and games—it seems easier to find enduring work from the past than today. Politicians, too, appeared more capable. To me, this suggested a greater prevalence of true thinkers, philosophers, scientists, artists, and leaders in both China and the West during that era. So, how is it that, despite unprecedented economic prosperity and technological advancement, we find ourselves spiritually and culturally stagnant in this new century?

I've read some of your articles, and you’ve pointed out issues with the insufficiency of the monetary signal and the flaws within capitalist systems. Could you elaborate on that?

Michel: Yes, I believe the exclusive uses of the monetary signal and its following commercial nature contributed to what you said about the cultural stagnant. The capitalism we have now is prioritizing the market above all else.

In the past, although we had the class come to power, it was always kept under. If you look at history, every civilization before capitalism, its main priority was always to keep the market in its place and make sure that it didn't become everything. Every civilization has done that until the 16th century. We had allowed markets, even thrived markets, but always embedded something that was higher.

The 16th century shift to market domination is deeply problematic. And now, this trend has reached its most extreme form. To go back to what you said in the beginning, which I think is a real problem. I think what we have in the West is this kind of systematic exploitation of lower human drives, like greed and hedonism. The system today is making us stupid, because if you want to sell something right, the best way is to appeal to what we have in common, which is violence and sex. So, they're going to program everything on TV to appeal, not to your higher drives, but your lower drives. That's a big difference from, even in a pre-capitalist civilization, where you have virtues, you have to learn. But now we're not learning.

935: It seems that once we're entrenched in this mode of production, we're compelled by the singular motivation—profit maximization and efficiency. This focus seems inevitably sidelines other essential virtues and non-monetary values. Essentially, why does marketization inevitably lead to such a tendency?

Michel: If we think about how value is created and valued in our current system, you will realize what is the problem. One of the key issues of our current value system is, our value comes solely from scarcity. Then everything becomes a commodity. It has to have a tension between supply and demand. And because the scarce commodity creates profit, so the system extracts what creates the scarce commodity. It's the only way to create value in our vision.

Before the 16th century in Europe, when it was toil economy, the dominant vision was land. Land creates value. Farmer gives some of surplus to the Lord, that makes Lord Rich. Then in maybe the 18th century, when it was industrial economy, we moved to the idea of labor as a source of value, please noticed that the labor is not as creative labor, but as a commodity. Like what Marx said, the abstract amount of labor. The labor value theory Is the abstract commodity value of labor, not labor like crafts, but like marketable.

What does this mean? Capitalism is a systematic elimination of externalities. Here's how it creates wealth. It extracts from labor and nature, making them commodities, sell them for a higher profit, that's wealth. And then everything else is a cost.

935:Is there any way to address the overlooked externalities?

Michel: In earlier times, the state was entrusted with overseeing public affairs, and as a result, it would typically step in to manage externalities ignored by the market, compensating for the costs through taxes. But now, the nation-state's role in addressing externalities is diminishing, partly due to the decline in national identity.

The liberal view assumed that if everyone acts out of self-interest, the market will naturally make everyone wealthier. However, history has shown that this doesn’t hold true. Because people realize you can't ask people to die for capital. Whenever that has been tried, it hasn't worked. For example, in 17th century Dutch Republic (which is essentially a merchant republic) had abolished the guilds, but the workers don’t want to die for the merchants, they no longer volunteered to defend Holland. The Dutch Republic eventually broke down. So, within a capitalist system, you need the nation as a new form of community that can be mobilized for defense. But in exchange, you have to give it something.

We've been undermining the nation. Like a lot of young people today, they don't believe in a nation at all. I don't know about China, but that is certainly happening in the West, the number of people willing to die for their nation would be marginal.

935: I understand how the government can play a regulatory role, guiding market development and addressing overlooked externalities. And it seems that in Western, it is not working in that way. From what you’ve said, it seems that perhaps we should reawaken people’s awareness of nations as a higher collective identity, so that we can break free from market domination?

In China, emphasizing the symbolic meaning of nation is always regarded as a dangerous tendency toward totalitarian, it may be effective in restrain market, but it certainly swings to the other terrible extreme.

Michel: Yeah, what you are concerned about is absolutely right. But what I am trying to point out here is that: yes, China and other collectivist countries can make a lot of wrong decisions for the whole, but they still posit the ability to plan for whole. That is the key difference that I want to point out and compare with the West. In the West, we are losing the ability to collective planning and action.

For example, I think China is collective in the sense that in China the land can only be leased but it cannot be sold. The village communes actually own the land. That's what I read on. That's a very important defense mechanism for the collective. That is what makes China so distinctive in my view. In the West, you have private reproduction of the ruling class. ‘I own something. It goes over to my children.’ And over time, as a rich family, I can accumulate. But I think in China, you can do that only to a certain extent. Because actually, it's a collective reproduction of the ruling class through the Communist Party. You have to make a career in the party.

While you do have billionaires in the party, but they're limited to 3% or something. Even though it's very capitalistic in many ways, they also do keep the private capitalist power. Maybe this will make you angry. But people like me, we still believe that there's an advantage to this. Because you can actually take care of the whole, even in a distorted way. Because in the West the problem is you can almost no longer care for the whole, like the US cannot build high speed railway. Because private interests just block it. Again, China can make a lot of wrong decisions about the whole, but you can still make decisions about the whole. You can have strategic visions and stuff.

It's kind of like macro governance. You try to engineer. What I'm trying to do is think at the micro governance level, where you can use the different institutions and their logics and think, what is the optimal way to do that today?

935: Given that the traditional nation-state model is no longer functioning, what alternative solutions can we find for the current system?

Michel: One of the things is to reinvent the monetary signals into something higher. You can have another point of view which I call contribution. Once someone has contributed, you can say this is a positive or negative contribution. This is socially ecological. Everything that's contribution creates wealth. If you're a mother or a father and you take care of your children, you're creating wealth. You're contributing to society by taking care of children and older people. If you clean the beach after an oil spill, you're contributing. It's not paid because it's not considered as a commodity.

I would like to mention the example of three different types of nurses. The first category of nurse are nuns in church, because nursing used to be a religious activity in Europe. These nuns organize the church hospitals, they get foods and everything they need, but they're not paid. The second category of nurses works in public hospitals, these nurses cost money. The last category of nurses works in private hospitals, they create value. So, although they are doing the same work, they have three different value propositions in capitalism: the nun is neutral, they don’t cost anything, but they also don’t create any economic value at all. As for the public hospital nurse, we have to pay taxes to pay for it. So that costs money. The third nurse is creating value for shareholders. They create GDP. So, ultimately, from a capitalist market perspective, the private nurse would be prioritized as they are most economically significant. The market will invest most of the resources in private sector and commodify the healthcare services.

But if you go down a level, you say no, these are all contributions. We should all count them. That's my proposal, to shift from a commodity regime to a contributory regime. A regime where you can count negative contributions like environmental damage and pollution or positive contribution like babysitting. All our accounting systems should be reformed for these non-monetary signals.

Rebuilding an unbalanced society

935: How exactly can we shift from a commodity regime to a contributory regime? Can we achieve this transformation through your proposal of global commons?

Michel: Yeah, I believe so. To be more precise about how we can make this shift, my proposal is to reinflate the commons, using it as a tool for equilibrium to restore balance between the market and the nation. So that we can break this market-domination situation.

Here is how I think about all these things. Among the human history, there is an interplay between the three social institutions: Markets, States, and the Commons. I think until 5000 years ago, the Commons was dominant, while the market was marginal or even non-existent in the tribal systems. But after we had civilization, markets and states became dominance. The power thus shifted from commons. And in a way, the power tension became a struggle between the market and the state elite. This tension restrained the two institutions, and it evolved over time.

Then in the 16th century in the Age of Discovery, I think with the Western system, it completely flips to a dominance of market capitalism. The typical thing about capitalism is that it completely or more radically eliminates the commons than previously times, which was kind of like a balancing factor.

The commons serve as a stabilizing mechanism within our societal equilibrium. When markets and states function effectively, the commons remain peripheral; but when markets and states fail, commons get stronger. Historically, this cyclical power shift has been evident. There are always periods of high growth or low growth, during the high growth period, the markets and states played dominant roles; while in low growth period, the commons provide a stabilizing cushion. This pattern was evident in both agricultural and early industrial economies, such as the 12th-century Song dynasty in China.

The way that power equilibrium functions is different when you have commons and without commons. When you have commons, it's the commons absorbs the crisis. For example, Commons are still working very well in Thailand. During the 1997 Asian financial crisis, approximately 2 million people left Bangkok, and many anticipated severe repercussions. But it didn’t happen. Because the in a way, Family Commons, the villages, the solidarity mechanism of these communities just absorbed the shock. When you don’t have commons, the crisis just hit you straight.

Now both in China and the West, the commons no longer really exist, so that mechanism for recreating equilibrium is gone. I'm not saying it's 100% gone, but it's problematic.

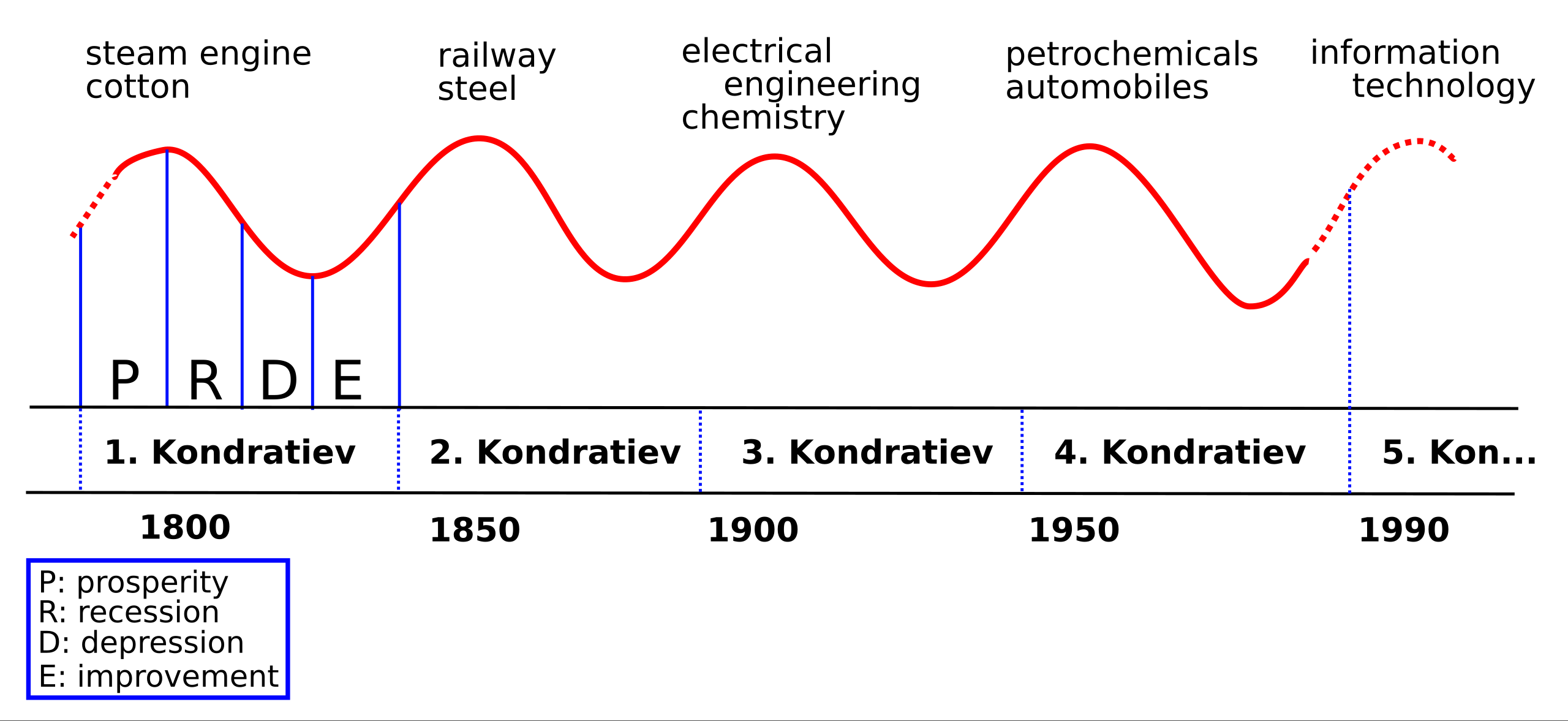

In Europe, the disintegration of the family is very advanced (In the US, this is even more). When there is no Commons, what replaces the Commons is the state, the state regulates the market. Normally, capital will try to appeal for more deregulation while state tend to do more regulation. This is interactive. Every 30 years, it's more or less like this: re-regulating the market, de-regulating the market, and re-regulating them again. Polanyi calls this ‘lib-lab’ like Labor dominates or the market dominates. This also resonates to Kondratiev’s cycle theory, a roughly 30 years cycle contains high growth, big crisis, slow growth and systemic crisis. This applies to the years 1873, 1929 and 2008. When the state is dominant, the state can keep the equilibrium within the state, but when capital becomes transnational, this regulation stops functioning.

The aforementioned cycle is typical to a capitalist society. China and Russia are a bit different. But basically it is still a swing between state and market. If you take the Russian Revolution as example, first you have the revolution, then you have war communism, which is the state only, everything is top down to fight, the whites and the Reds fighting each other. When the Reds won, they actually reintroduced the market. It's called the New Economic Policy(NEP). If you look at Soviet pictures in the 1920s, it worked very well. You look at films in 1920s in Odessa and it looks like Paris. It's just like in China now. But then Stalin basically reintroduces the state. And then it collapses.

In China I think it's the same cycle, except that war communism lasts much longer until Deng basically introduces the equivalent of NEP. And then with XJP, it is recentering around the state again.

Regardless of the West or East, we are in a transnational capital blockage. The normal equilibrium mechanism is not working any more, you cannot do lib-lab (liberal-labor) within a nation state when you have transnational capital, because they'll just swap the nation state out, like they close the banks, you can't find money, and then hyperinflation happens. It also doesn't matter whether you're right or left. It’s when you go beyond their interests, the transnational capital will let you know you can’t do this.

Now the way that the Eastern and Western governments figure out to resolve this, is by inflating the states. But I don’t believe that is the right way.

In the east, there are Eastern Eurasian bloc and the BRICs, which is kind of a coalition now, you have recentering towards the state. We are disciplining the market on the revision of interstate system, although with a new injection of like civilizational values: the Confucian institutes in China. We talk about the civilization state now, not the Westphalian state, but the civilization state. It's like reinjecting identity from the past to give more content to the state. I'm not saying it's working, but that's what they are trying.

In the West, I think the Western idea under the leadership of the World Economic Forum is to create a global system of multi-stakeholder coalitions. But it is a coalition under the leadership of finance. You have financial institutions, weak nation states and approved NGOs, they run everything per domain. That's the plan in the West. In the West, you also have people who don't agree with this. These are the right-wing populists. They also want to restore the nation state. But as you notice, it stays within the market state duality.

All these attempts, they don't think about the commons at all. It's not in there.

The only way to reinstate this equilibrium, in my view, is to reinflate the commons, not the state.

If you inflate the state, then you have a world government, but if you bring in the Commons then you have a third option, which is to make the commons the regulation of both the market and the state. The commons is the protective and regenerative institution. If you look at history, commons are the healing mechanisms. Today if you take a picture of the world, you can see Japan, Austria, Switzerland is so green, why? Because the mountains are managed as a common, the local people don't allow the destruction of their forests. But if you privatize it, the local people won’t be able to do that. Liberals think they can find the balance between economic and environment, because the market is self-healing and self-regulating. But the transnational finance is not, they just go somewhere else. They just abstract. Even when they try to do so, it is distorted. For example, if you have a real forest, they say ‘let's buy carbon credits’, they destroyed that real forest, then buying up carbon credits somewhere else. Actually, that's from a real forest that also already exists. They just pretend and redefine it and sell the carbon credits. So, they destroy a real forest, and then fake a new forest which already existed anyway. That it's because they only look at the monetary signal.

System scalability: creating surplus value

935: I agree with what you said that commons are the protective and regenerative institutions. Their preserving nature reminds me of the cooperative. Unlike transnational capitalist corporations, cooperatives focus more on preserving local communities, human values, and the environment. In this sense, cooperatives seem to reflect the same ideals as the commons.

However, despite these virtues, the system is still dominated by the 'more efficient' capitalist market, there is little room for such preserving institutions.Besides, the cooperatives are usually at risk of being eaten up.

I fully understand the necessity to introduce commons or cooperatives, but how exactly can it break the current suffocating system?

Michel: Here's how I think about this. Firstly, I think you can have both cooperatives and capitalist companies in the market. Secondly, cooperatives have their own competitive advantages that, in certain circumstance, it would scale its own system that allow it to be more supreme than the current system. There is a macro historical thinker called Carroll Quigley. He has a book called Evolution of Civilizations. He says the key to the success of civilization is an instrument of expansion. It is basically about how do you create surplus.

Commons is good at creating surplus. For example, why monastery is so successful, especially in the dark Ages? That is because all the surplus they create goes into the expansion of the system. You have no ruling class that takes up the luxury. In monastery, if you have 64 monks, half of them would need to leave and find another place and restart everything, it is like the bees. All the surplus that bees create goes to their own system. They just duplicate like viral. It's a viral expansion mechanism. Basically, if there are too many bees, it will be cut into two, the queen bee has to find another place. That is also how the monks did it.

An instrument of expansion is a way to create surplus and then invest it in the expansion of your system. In Europe it would have been feudalism that included the monastic institutions, then commercial capitalism and then industrial capitalism. Carroll Quigley says it gets corrupted when it becomes institutionalized and only thinks about itself and not about society. So, feudalism becomes chivalry, commercial capitalism becomes mercantile capitalism, and industrial capitalism becomes monopoly capitalism.

Surplus is how human beings basically create the world. If you are totally egalitarian, you have no surplus. And that means you're going to lose because anybody else with more surplus will be stronger than you. So, you must create more or less egalitarian institutions as you can.

935: So, what are these surpluses?

Michel: Everything. Everything you get from human labor and nature. Surplus are the virtues and values from ourselves and our environment. Essentially, it is about how you build with resources.

In terms of human labor, I’m still a Marxist in that way. I think human labor is the creative capacity of the human being to transform nature, and to bring beauty and consciousness to the world, I still believe in that. With this being said, I don't think we should go back to indigenous societies where we live off, and don't create anything. This it's inherent to our human condition

As for nature, we have to respect the balance of the natural world, that's what capitalism cannot do. That's why we have to change it. I believe that the success of monastics is that they believed in something. For them, to create the monastery is to recreate Eden. The eastern monks, the Buddhist monks, they have a communism of consumption only. But the Western monks had a communism of production. They shared everything when they were working. They farmed, they crafted, they prayed, and they studied in one integrated community. When it was working well, their aim is to create the true, the good and the beautiful in the world. It's a very high standard working on your virtues, on yourself as you work with the community. Unfortunately, it eventually gets corrupted all the time. But it can last for quite a while, that's good enough.

935: As you said, the ‘monk strategy’ seems gradually collapse. Will this happen to global commons as well? How may it work today?

Michel: The way it works is by what I called the Cosmo-localism. Most people are local, even today. If you look at the mobile phone analysis in the US, 95% of people don't leave their city. They don't even travel, a lot of people don't move. They're connected to their local, their family, whatever.

So, those people who don’t move create resilient communities that produce healthy food, renewable energy. In the communities, there are also people that are nomads, who move around to help local communities with the collective wisdom of the collective system, who transfer innovations, teach, and know IT. These people can help the locals coordinate better. We need both types of people. Both of them should be embedded in networks of productive communities.

If you look at religions, you have the local priests. But you also have the wandering monks. Some people are rooted in a place, and some people bring knowledge from the outside. The global commons we need today might be such a system.

935: So to wrap up here, you see a better future with a balance and a coexistence between market, states, and global commons?

Michel: Yes, the question is how smooth or how hard it will be.

If you look at history, I think you can see that there is a drive for more complexity and cooperation, even in the universe. For example, before human beings, when matter becomes more organized, it creates life. Afterwards, life creates more complex beings and ecosystems. I think this is not only the anthropic principle but is also an entropic principle.

Humans represent the most complex form of this entropic principle. In this nature process of entropy reduction, we must do it in a responsible way. I believe building commons is one of the responsible approaches. And now, as the digital techniques come in, they brought the capacity to reintroduce externalities in our management and treatment of resources.

7k: Another practical question is about how do you do your case study? In your book and the articles, some of the practices that you mentioned as case studies failed afterwards, for example the ‘Transitional Town’. How do you think about those failed examples? Did they disproof your previous assumption?

Michel: I used to work with ten people. I didn't do much case studies myself, but I travel a lot. From 2005 to 2018 I was increasingly on the road, up to five, seven months a year. So I would see a lot of things. I would really go to Kathryn Tickell Cooperative and places in Brazil and Ethiopia. And I would spend 3, 4 or 5 days with these people and they would tell me about their problems. I didn't do much case studies, but I did a lot of observation. And it was not just desktop observation, I was physically present in many places. As we got more successful, we got the P2P lab. And they did case studies. They would actually do peer reviewed. I did also write a lot of peer reviewed articles, but they are not case studies, they are the theoretical ones. What my colleagues would do is actually write case studies. It's true that I cannot follow up everything. So the weakness of my wiki is that it cannot follow up the failures.But thinking about startups, 99% of startups would fail. But it's still working as a system. And I think it's the same with the Commons. A lot of Commons would fail, but overall it has grown a lot.

But also, you're right. I think we should spend more time on the failures and learning from the failures. I guess because I'm just one person, I really focus on things that are working at a certain moment in time, and then maybe exaggerate a little bit. It's like when you're an entrepreneur and you need capital, you're not going to say oh it may still fail. You try to present the best case, the best possible scenario, it was not inventing out of nothing. It is about based on what you see, and you believe this could be going this way.

7k: So what do you think of your role and place in this transformation process/ movement?

Michel: Well, compared to the past, I've become a lot more modest. But in a way, I don't think there's enough people thinking about how do we shift to this post-industrial (period), I sometimes even call it post-civilizational. It's about thinking the shift and looking at the possibilities for further emancipation within that process–In that sense, I'm still kind of within a Marxist tradition or maybe even a Christian tradition–How can everybody have a dignified human life.

Christians are the best in the best sense of the world, we're all children of the same God, so we have to love one another. I'm not talking about the practice here. I'm talking about the idea. And Marxism was originally about the universal brotherhood of labor. It's like everybody in the world works, and we all create value, and we should recognize that value. That's the original. Whatever happens afterwards when they actually try to do it. That's another question. But I think this dream that we have, I think that is worth preserving. I think it's very black right now. But, you know, yin yang, always the little dots of light in the dark.

Uncommons

Reporter/Translator: 7k&935

Edit:0614

The sources of the images in the text have been identified

Who we are 👇

Uncommons

区块链世界内一隅公共空间,一群公共物品建设者,在此碰撞加密人文思想。其前身为 GreenPill 中文社区。

Twitter: x.com/Un__commons

Newsletter: blog.uncommons.cc/

Join us: t.me/theuncommons

Discussion