加密飞行 Vol.7 | 黄孙权专访:社区先于规模,合作社与DAO

“技术要能够造成进步,一定是跟社会变革力量有关。”

Crypto Flight Vol.7|Community Precedes Scalability—Cooperative and DAOInterview with Huang Sunquan

Abstract: Progress requires social movements, and social movements direct technology to a better place.

"Crypto Flight" is a series of interviews by Uncommons, focusing on pioneers active in the Ethereum and crypto world. It documents the reality of the crypto space and produces diverse perspectives, using conversation and everyday language as methods to distill distant and far-off truths. Inspired by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's Vol de Nuit (Night Flight), it symbolizes the challenge and exploratory spirit of cypherpunks and crypto citizens as they venture to the ends of the world.

合作社是什么,和DAO有什么不同What Are Cooperatives, and How Do They Differ from DAOs?

让Web3重回地方价值

Reconnecting Web3 to Local Values

Web3作为Web2的替代:ownership到property

Web3 as a Replacement for Web2: From Ownership to Property

Coop—一种中心化的小社区Social Token尝试

Coop—A Centralized Small-Scale Social Token Experiment

社区先于规模

Community Precedes Scalability

网研所的研究历史变迁和自己的目标:合作社与UBI

The Evolution of the Institute of Network Society’s Research and Its Goals: Cooperatives and UBI

About

黄孙权 Huang Sunquan

台湾大学工学博士,学者、策展人,艺术家。曾于港台多所大学任教,现为中国美术学院教授,跨媒体艺术学院网络社会研究所所长。

Doctor of Engineering, Taiwan University, scholar, curator, artist. He has taught in many universities in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and is currently a professor at the China Academy of Art and director of the Institute of Network Society at the Institute of Transmedia Art.

7k

技术与媒介研究者。关注货币史与加密货币行业,密码朋克文化。

Technology and media researcher. Focuses on monetary history and the cryptocurrency industry, cypherpunk culture.

935

心在20世纪,身在21世纪,思绪在22世纪的加密运动与技术哲学研究者。

Mind in the 20th century, body in the 21st century, mind in the 22nd century crypto movement and philosophy of technology researcher.

治理的尺度:对比合作社与DAO

The Scalability of Governance: Cooperative vs. DAO

合作社是什么,和DAO有什么不同

What Are Cooperatives, and How Do They Differ from DAOs?

935:合作社一直是你研究和工作的重心。你认为它能如何抗衡Network effect?比如,苏联时期的女性共产主义者罗莎·卢森堡曾在《改良还是改革》里表达过这样的观点:如果我们没法彻底改革资本主义的市场逻辑,合作社只能是一种短暂的改良。像工人合作社这种生产模式,一旦要加入市场竞争,依然会不可避免地出现分工和追求市场效率,最终也只会演变成另外一家资本公司,西班牙的蒙德拉贡(Mondragon)合作社好像也是这样。

935: Cooperatives have long been central to your work, but how do they resist network effects? Rosa Luxemburg, in Reform or Revolution, argued that without overthrowing capitalist market logic, cooperatives are merely temporary fixes. For example, worker cooperatives competing in markets inevitably replicate capitalist hierarchies—like Spain’s Mondragon, which some say became just another corporation.

黄孙权:不完全是这样。合作社的确就是一个公司,但是它最高管理阶层的工资跟最低工资之间不能超过十二倍,这是没有任何一个公司可以做到的。蒙德拉贡合作社曾经考虑到中国设厂,唯一否定的原因,是他们的社员要求在中国设厂的工人工资要跟西班牙一样,他们没法做到。这种事情不可能发生在其他公司。

Huang Sunquan: Not entirely. Cooperatives are companies, but their wage gaps between the top and bottom tiers are capped at 12:1—unthinkable in companies. Mondragon once considered expanding to China but rejected it because members demanded equal pay for Chinese workers as in Spain. No company would do that.

合作社不是一个颠覆或革命的方案,但它会在资本主义的情况下,让我们可以活得稍微舒畅一点。它就是一个工人拥有公司的东西,并且所有的Share holder,不管你持有股份的多少,都是一人一票的权利,Shareholder与 Stakeholder是一体的,这跟公司股份制完全不一样。并且按照国际合作社的标准规定,30%的收益必须拿出来做有益社区的事情。

Cooperatives aren’t revolutionary solution, but under capitalism, they let us live slightly better. Workers own the company, and each member has one vote, regardless of shares. That is to say a shareholder is a stakeholder, unlike corporations where shareholders dominate. Also, by international standards, 30% of profits must be used for the community's benefit.

这远远是DAO没有的。Web3的所有的提案都是按照你拥有多少Stake来决定,这不就是公司股份吗?DAO基本上就是一个公司,在互相不认识的基础上相信数学机制的判断,然后投票。这个提法一点都不新,为什么倒变成年轻人的期望?我一直不懂这件事。

You can’t see this in DAOs. Web3 governance is stake-weighted—isn’t it identical to corporate shares? DAOs are just companies, with people not knowing each other and voting on the trust for math over people. Why is this seen as revolutionary? I don’t get it.

我原来和南塘合作社合作了很久,还为他们做了一个参与式设计的合作社经营中心,后来因为地方政府不支持他们而没有盖成。当时合作社的杨大哥欠了很多钱。 后来南塘DAO说想去帮忙,帮忙1年多就去了七个人,每天给20工分,相当于2块人民币,一个月大概给南塘140人民币的收益。我觉得不要做这种没有意义的事情。

I worked with Nantang Cooperative for a longtime, and even once did a participatory-designed cooperative center for them, yet local government opposition killed it. The leader, Brother Yang, was deep in debt by then. Later, Nantang DAO offered help: seven people worked for a year, earning 20 workpoints daily (worth ¥2), totaling ¥140/month. I think that’s a little pointless.

南塘合作社就是非常激进的,因为四千多个村民都是南塘合作社的成员。南塘是很大的,有四十几个村,每个村都有很多干部出来开会,我参加过很多次:因为每个村种同一种作物会导致这个作物在市场上贬值,所以他们会商量,如果这个村今年种枣子,那隔壁村就不要种枣子。这是非常有机的,所有的东西都是投票投出来的,一人一票。而且杨大哥之前还给他们读了一本叫《罗伯特议事规则》,让农民学会说我要开会,我要先举手,遵守规则。他们把它叫做《萝卜白菜规则》,这样更容易记。他们是经过20年的磨炼才变成合作社。

Nantang Cooperative is very radical—4,000 villagers are members across 40 villages. They coordinate crops to avoid market saturation: if one village grows dates, neighbors don’t. Everything is voted on, one person, one vote. Brother Yang taught farmers Robert’s Rules of Order, which they renamed “Radish-Cabbage Rules” for simplicity. It took 20 years to build such a cooperative.

935:作为一个密切观察DAO3、4年的旁观者和社群参与者,我大概知道让一切协作自动化的想法目前还是不大可能。人们想要弄出很多量化的规范,最后发现无法穷尽,此外也有很多无法量化的东西。但在DAO的视角看来,之所以现在所有的实践走到了死胡同,是因为治理还没有做到百分百完善,他们似乎有一种对治理的痴迷。我不知道我这种感觉是不是正确的。

935: As a DAO observer for 3-4years, I know fully automatic cooperation is still impossible. You have to make many quantifiable metrics, but they are endless, let alone many things that cannot be quantified in the first place. However, DAOs seem to obsess over perfect governance, but maybe this perfectionism is a trap.

黄孙权:是。DAO这个东西,讨论所有的机制跟治理,大部分是为了让它自己的币有价值,持有币才可以参与讨论,这是一个由金钱驱动的假民主体制。SeeDAO虽然没有发币,但是他们拿了很多Funding来鼓励这个DAO。他们也做很多NFT,当作成员去Discord讨论的门槛。

Huang Sunquan: Exactly. Most of the debates over a DAO’s governance exist to boost its token value. Participation requires holding tokens—a money-driven pseudo-democracy. Even SeeDAO” which avoids tokens, relies on grants and NFTs as Discord entry tickets.

让Web3重回地方价值

Reconnecting Web3 to Local Values

黄孙权:我们现在要做黄岗村的乡建。黄岗村的鼓楼系统特别可爱。他们的小孩出生以后,一定要上山找一棵跟小孩一样的树,等小孩长大结婚以后,这棵树也长大了。18年后把这个树砍了,当小孩婚嫁时的家具礼物。甚至是等人死了以后,这棵树可以做成棺木。但这些文化保存都非常难。那边有一大堆墨师,他们没有任何建筑学基础,用自己的地方性语汇与构件图示来制图,按照自己的方法去判断树的生长和鼓楼的高度。那里的每个村都有一座鼓楼,每座都有不同的高度与设计图案。但现在这些墨师都面临失业,因为现在少数民族区里比较少人做纯木头的建筑,全部都被现代建筑取代了。

Huang Sunquan: We are now helping Huanggang Village, where the drum tower tradition is beautiful: When a child is born, a tree is planted. At marriage, the tree becomes furniture; at death, a coffin. But these traditions fade and they are hard to preserve. Local carpenters, using vernacular methods to design drum towers, face unemployment as modern buildings replace wood.

所以我希望可以有一个加密货币或者NFT来当做保值的工具,并且卖这个Token的钱不是回到我身上,而是回到这些墨师,让他们可以更好地做这些事情。但是我参考过非常多例子,比如City DAO,日本的一些案例等等,都不太成功。因为购买那些项目的Token并不是真的想要支持一个公共的物品,他们就是为了要转卖、收集。

I want to issue a crypto or NFT to fund these artisans, instead of arbitrage for its owners’ benefit. Similar projects like City DAO fail because buyers just flip tokens or collect, not support communities and commons.

935:我觉得重点是,NFT一旦对外规模化地去发行之后,买NFT的人并没有很强的Incentive让花出去的钱能够回馈到在地的社群。我之前去过比利时一个叫斯帕(Spa)的小镇,小镇旁边有一个F1赛道,每年都会有一场F1比赛在那边举行,全球各地的车迷过来看几天比赛。这些车迷会有住宿,吃喝,交通的需求。所以斯帕小镇上一个村的几个老爷爷、老奶奶每年就自发组织起来,到比赛季的时候把村里的几块场地空出来,让车迷可以在那边支帐篷或停房车。他们也在那边提供食堂,提供来往的交通,提供一个小酒吧给大家喝酒。他们食堂里都是自己村的人养的牛做成的汉堡,调酒也是自己村里面发明的配方。每年村民们都自愿集结起来做这件事情,他们不领工资。在这场活动里赚到的钱,不管是收住宿费的钱,还是那些消费产生的钱,都留下来作为村里面的公共基金,要么拿去做一些村里基建,要么就是留起来给村里的小孩上大学用。

所以,如果买NFT的人最后的目都是想继续流通,他们没有很强的Incentive让买这个NFT的钱回归到在地的社群中去。而对这个小镇的人来说,村子里这样的体系在代际和一个一个家庭中互惠,所以他们有很强的Incentive让这些钱回到他的大集体上。

935: I think the point is when NFTs are issued at scale, buyers are not incentivized to repay local communities. I was in Spa, Belgium, where villagers host F1 fans annually. They provide campsites, food, and transport, reinvesting profits into community funds. Their incentive to repay the community is passed family by family, generation by generation. However, NFT buyers are just aiming to circulate their possession.

7k:你提过DAO和合作社一个很大的区别就是利益相关。DAO是需要你不利益相关,但是合作社是需要你有利益相关。

7k: You once mentioned that DAOs demand disinterestedness while cooperatives require interestedness.

黄孙权:有点像是我在今年年会开幕致辞里说的:今年得到诺贝尔经济学奖的Daron Acemoglu 和 Simon Johnson,他们在著作《权力与进步》里一个非常基本的看法是“技术不一定代表进步”。 技术要能够造成进步,一定是跟社会变革力量有关,社会变革力量出现了,技术才会让社会往好的方向去。这个看法我们其实已经很熟了,但是Web3的人不知道有没有接收到这个讯息。

Huang Sunquan: As I mentioned in the opening speech at the conference of Network Society this year: Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson’s basic argument in Power and Progress is “Technology doesn’t equal to progress.” Progress requires social movements, and social movements direct technology to a better place. I don’t know whether the Web3 community has grasped this.

其实有很多这样的例子,它们跟Web3一点关系都没有。譬如,台湾有一个地方叫司马库斯,是一个两百多个人的原住民村落。它在新竹的山上,很偏远,但那应该是我看过最牛的合作社了。这整个村都是合作社,因为他们原住民本来就有这种共享的精神。由于每天有非常多人去观光,有些人家里比较有钱,所以他们开民宿,开餐厅,但其他那些没开民宿和餐厅的村民就觉得为什么要让别人来打扰我们的生活?他们后来规定每天进村的人数要有限制,并且他们有一个合作社式的组织委员会,将这些经营得赚的钱,提成到这个集体里重新分配。因为这是村集体负担的社会成本、外部成本,不能只是让开餐厅或开民宿的赚钱。我看过太多中国乡建,就是开民宿的赚钱,开饭店赚钱,一般村民跟它根本没关系。

Take Taiwan’s Smangus (司馬庫斯) as an example, an Indigenous cooperative village with around 200 people. It’s located in the mountains of Hsinchu, a remote area, but it’s probably the most impressive cooperative I’ve ever seen. The entire village operates as a cooperative, rooted in the Indigenous community’s inherent spirit of sharing. Due to the influx of tourists, some families running guesthouses or restaurants profited more. But why should outsiders disrupt their lives? They eventually imposed daily visitor limits and established a cooperative committee to pool a portion of earnings from these businesses for collective redistribution. This addressed the social and external costs borne by the village, ensuring profits weren’t monopolized by a few. I’ve seen too many rural development projects in China where guesthouses and restaurants profit while ordinary villagers gain nothing.

他们(司马库斯)甚至做到有一种非常完整的机制,给要到新竹或台北市去念大学的小朋友补助。因为山上没有高中,他们的学生高中就要下山了,所以他们在山下买一栋房子,所有的高中生可以住在那里,只有一个要求:每个月请你回家乡看一下爸妈跟环境。

The Smangus community even developed a comprehensive support system for youth attending university in Hsinchu or Taipei. Since there are no high schools in the mountains, students must move downhill for education. The village purchased a building in the lowlands to house these students, with one condition: Please return home monthly, to visit your parents and the village.

这是合作社。根本不用什么新的技术,他们就可以完成这个事情。他们是可以自负盈亏的村落,村子里完全不搞任何别的东西。这不就是最好的梦想么?这些东西都有了,根本不用Web3就已经有了。

This is cooperative. They don’t need any new technology to make it work. The village is self-sustaining, financially independent, and free from unnecessary complications. Isn’t this the ultimate dream? All these things already exist—no Web3 required.

基本上所有加密货币,唯一能够解决的问题是在流通过程中遇到的困难,但其他事情并没有被解决。而你越解决流通问题,资本越容易流动,资本主义就越兴盛,有钱人就越容易逃税,对穷人来说根本没有任何帮助。所以我们整个加密货币行业在干嘛呢?如果就是解决资本主义的积累困难,这不是一个非常反讽的结局吗?一开始不就是因为资本主义遇到大灾难,所以我们才开始搞加密货币吗?

Fundamentally, the only problem cryptocurrencies solve is friction in circulation. Nothing else. And the more you streamline circulation, the easier capital flows, the stronger capitalism grows, the richer evade taxes, and the poorer gain nothing. So what is the entire crypto industry really doing? If it’s just easing capital accumulation for capitalism, isn’t that a bitterly ironic outcome? Wasn’t crypto born from capitalism’s crises in the first place?

Web3作为Web2的替代:ownership到property

Web3 as a Replacement for Web2: From Ownership to Property

7k:我们刚刚举了很多物质生产的案例,而Web3其实最初是想替代Web2的网络平台。它希望提供开源的,有信息有所有权的,作为一种退出选择(option-out)的平台,通过区块链把数据的所有权转到用户这边来,给出了一种新的互联网生产关系。您怎么看这个观点?在很长一段时间内,你也一直在实践平台合作主义。

7k: We just discussed many examples of material production, but Web3 was originally conceived as a replacement for Web2 internet platforms. It aims to provide an open-source, information-ownership-enabled platform—at least as an opt-out alternative—using blockchain to transfer data ownership to users and establish new internet production relations. What’s your take on this view? For a long time, you’ve also been practicing platform cooperativism.

黄孙权: 一方面来说,我觉得Web3的发展可能有点机会,是因为现在互联网已经不互联了。特别是中国,一个平台跟其他其他平台都不互联。所以Web3有穿透这些不互联的东西的可能性。但是,为什么我要觉得在网上发的东西有价值,而且我应该拥有它们?

Huang Sunquan: On one hand, I think Web3 might have some potential precisely because the internet is no longer interconnected. Especially in China, platforms are siloed from one another. Web3 could potentially penetrate these isolated systems. But why should I believe that what I post online has value, and that I should own it?

回到2000年,我写东西就是觉得,全世界都没人报道,我写出来就是让更多人看到。因为我的目的是要让大家知道这个事实,我怎么会想到看我的东西需要你付我钱?大家根本不会想这个事。可是当我想这个事儿的时候意味着什么? Ownership的背后并不是你要拥有所有权,而是所有权可以辅助于资本积累,通过某种机制让我的所有权或财产(property/ownership)有价值。现在Web3上很多的开发都是基于开源。最后你在上面写一篇稿子,你说你要ownership。我也没有觉得不行,但是它有点好笑。

Back in 2000, when I wrote things, it was because no one else was reporting on them. I wrote to reach more people. My goal was to inform people of the facts—why would I expect anyone to pay to read my work? No one even considered that back then. But when I start thinking about ownership, what does that imply? Ownership isn’t just about claiming rights—it’s about how ownership facilitates capital accumulation, creating value for my property through certain mechanisms(property/ownership). Much of Web3’s development is built on open-source principles. Yet when you write an article on such a platform and demand ownership, I don’t necessarily oppose it, but it feels a bit absurd.

7k:但是另外一方面,我也不希望这个ownership是平台的。

7k: On the other hand, I also don’t want this ownership to belong to platforms.

黄孙权:那你就不要在平台上写东西不就行了,回到2003年那个Blog时代,why not?

Huang Sunquan: Then just stop writing on platforms. Return to the blogging era of 2003—why not?

我不是质问你,我只是通过非常简单的问题问我自己:这些东西其实并没有帮助我,起码没有让我看到2000年的Indymedia,或者2002年左右那个Blogsphere的力量。Web3对我来说有点虚幻了。

I’m not interrogating you—I’m asking myself through these simple questions: These things haven’t helped me, at least not in the way Indymedia in 2000 or the blogosphere around 2002 did. Web3 feels illusory to me.

Coop——一种中心化的小社区Social Token尝试

Coop——A Centralized Small-Scale Social Token Experiment

黄孙权: 虽然我们也发Coop:你有Coop可以看到整个网研所出版的所有论文,超过几个Coop你就可以看到我们的杂志。订我们的东西,或者当我们的义工就可以拿Coop,它就是一个内部小循环系统,我也不想做大,也不想在市场上交易。我们互相认识彼此。你知道我是谁,我也知道你是谁,我们互相交换劳力。它是一个非常互助的,互惠的东西。它就是非常小,但无所谓。现在拥有Coop的人的总数只有500多个。

Huang Sunquan: Although we’ve also issued Coop: If you have Coop tokens, you can access all papers published by the Institute of Network Society. With a few more Coop, you can read our journals. And you can earn Coop through Ordering from us or volunteering for us—it’s a small internal circular system. I don’t want to scale it up or trade it on markets. You know who I am, I know who you are, and we exchange labor. It’s a mutual aid system, reciprocal and small-scale. That’s fine. Currently, only about 500 people hold Coop.

Social token的概念比较像我们现在正在做的事。因为它是小规模的,一开始其实为了满足艺术学院学生的需要。比如说我在做作品的时候,我去问学弟学妹,他们都会来帮忙。其实每个地方都有这种非常密切需要彼此帮忙的事,那我们就需要一个计价系统或记帐系统,把贡献记得就好了。以前有一阵子我在上课,我们在Discord上有公开,但是你要有一个Coop才能听。后来Discord有几十号人会听我这个课,虽然他完全看不到我的PPT,但只要是我讲的,他们也愿意来听。这就是小规模的社群反而会有点意思的地方。

The concept of a social token aligns with what we’re doing. It’s small-scale, initially designed to meet the needs of art school students. For example, when I’m working on a project, I ask juniors for help, and they come. Every community has these close-knit mutual aid dynamics—we just need a valuation or accounting system to track contributions. Once, when I taught a class on Discord, it was public but required Coop to join. Yet dozens of people attended by Discord, even though they couldn’t see my slides—they came just to listen. That’s the charm of small communities.

大的规模我绝对不敢想象,但小规模我觉得可以做到。譬如说,我今天公布一个硬性的要求,要求以后所有要考网研所的学生都要有Coop。每年几百个人来考我研究生,我们上的课,我们做的东西都要Coop。所以你就要慢慢想办法,获得Coop,比如来帮我们做义工,翻译等等。透过这个互惠的方式,让大家知道这个Token有一种特定的社会责任存在。那我就可以one by one地产生影响。

I can’t imagine scaling this up, but in small-scale? Absolutely. For instance, I could mandate that all applicants to our institute’s graduate program must hold Coop. Hundreds apply yearly—our courses and projects would require Coop. They’d have to earn it through volunteering, translation work, etc. This reciprocity would embed the token with a sense of social responsibility, creating impact one by one.

因为我们都互相认识,我们试图在这种小范围里收集全世界非常好的艺术创作跟纪录片,或者是Nathan Schneider在科罗拉多州搞媒体实验室和民主机制,或者是邱林川在新加坡,我们这次遇到的那个Cheryll在菲律宾等地(以上均为历届网络社会研究所年会的发言者)——你每个地方都可以这样做,如果越多像Coop这种形式,它就越Make sense。然后最后我们就可以互相谈对价。

Since we’re all connected, we’re gathering exceptional global art, documentaries, and projects like Nathan Schneider’s media lab and democratic experiments in Colorado, Jack Qiu’s work in Singapore, or Cheryll in the Philippines (all past speakers at Network Society Annual Conferences). The more communities adopt systems like Coop, the more feasible it becomes. Eventually, we could do price consideration between communities.

这可以回到一个非常古典的讨论:蒲鲁东在巴黎左岸搞工人运动时,希望工人的薪资不要用国家的货币,而是自己发行货币。马克思就骂了他,因为这个货币是没有办法流通的。现在可能有一种新的技术,可以做到对价和流通(虽然对价的方式有很多种)。以前对价是不可能实现的,所有的社区货币最后倒闭的原因都是因为它们没有办法流通,出了这个社区就没用了。但现在可以有不同的社区货币同时发行,然后相互之间对价。

This circles back to a classic debate: During the anarchism movement, Proudhon advocated paying workers with community-issued currency instead of state money. Marx criticized this, arguing such currency couldn’t circulate. Today, new technologies might enable valuation and circulation (though consideration methods vary). Historically, community currencies failed because they couldn’t circulate beyond their niche. Now, multiple community tokens could coexist and exchange.

真心话来说,我还是希望可以把Coop变成像淘宝一样。我想要实现一个很简单的例子,就是在这个网站里我可以用Coop买卖东西,这是历史上第一个这样的网站。像加密货币搞那么多(项目),没有一个可以做到像淘宝一样。比如用Coop,我可以卖我的劳力,卖我的东西。你看中本聪写的那个第一份白皮书里头,它谈的是个人对个人的支付系统,它没有那么伟大,它就是解决我们日常生活的支付。可是这么简单的事情为什么大家现在还没有没有办法实现呢?我其实不太知道为什么。

Honestly, I still hope to make Coop as functional as Taobao. I want to create a simple example—the first website where people buy and sell goods using crypto. Despite countless crypto projects, none have achieved something as practical as Taobao. With Coop, I could sell my labor or goods. Look at Satoshi’s original whitepaper—it proposed a peer-to-peer payment system, nothing grandiose, just solving daily transactions. Why hasn’t anyone realized this simple vision yet? I truly don’t know.

解法的探讨和Web3批评

Explorations of Solutions and Critiques of Web3

社区先于规模

Community Precedes Scalability

7k:货币系统已经联系了全球,给了我们一种Global的想象。我们不是用DAO,用这些治理模式投票,我们就是用购买,在用法币投票。我个人希望Web3能提供与全球资本主义抗衡的全球尺度上的治理模式。很多人强调 Web3有提供Scalability的潜力。社区代币之间通过Web3的对价系统实现流通不正是Scalability的体现么?DAO实际上也以提供一种具有Scalability的治理模式为目标,只是很多DAO现在更像是一个小社群。

7k: Monetary systems already connect worldwide, giving us a vision of "global". When we’re not using DAOs or governance models for voting, we’re still voting through purchases using fiat currency. Personally, I hope Web3 can offer governance models at a global scale to counter global capitalism. Many emphasize Web3’s potential for scalability. Isn’t the circulation between community tokens via Web3’s exchange systems precisely scalability in action? DAOs also aim to provide scalable governance, though many currently resemble small communities.

黄孙权:蒙德拉贡合作社(Mondragon)有几十万人,你要说Scalability,这算不算大?我觉得这些问题都非常好,你在逼问我一直想不通的事。但是假设我们不要Web3这个概念,我们看世界上已经成立的这种共治模式,最好的就是巴西的阿雷格里港,他们用公共投票来决定城市预算的,但一旦这个城市超过三十万人就有点难操作了。所以其实已经有成功的例子,根本没有Web3也可以这样干。所以你希望有多大的Scalability呢?

Huang Sunquan: The Mondragon Corporation has hundreds of thousands of members—is that a scale large enough? These are excellent questions, pushing me to confront unresolved issues. But if we set aside the Web3 label, look at existing co-governance models: Porto Alegre in Brazil uses participatory budgeting via public voting, though it struggles once the city exceeds 300,000 people. Nonetheless, successful examples already exist without Web3. So how much scalability do you really want?

我认为,要先有Community的就建立,Community之内的Circulation成立以后,我再在外头讨论它的Scalability。如果最基本的做不起来,你刚刚想的那一步就没有用了。譬如说,如果你是个劳动合作社,我们的Coop只能看书、买书,劳动合作社他们不需要书,他为什么跟我们交换?这时候才有Scalability的问题。但这种对价是最难的,因为每个社区都会有真实的需要。

I believe we must first build communities and establish internal circulation before discussing external scalability. Without foundational success, grand visions are useless. For example, if our Coop tokens only allow access to books, but a labor cooperative has no need for books, why would they trade with us? That’s where scalability challenges arise—inter-community valuation is hardest, as each has unique needs.

韩国的合作社是在亚洲最进步的,因为有三个人就可以成立合作社。他们有非常多的妈妈、托儿所,我们三个妇女我们就可以搞一个合作社,韩国政府会补助。比如我是全职妈妈,工作会很辛苦,我跟我周围的人说来帮我带小孩,我去工作。一开始是三个妈妈,后来是有几百人,然后真的是可以轮流照顾我的孩子。这是从小就开始慢慢找到的,我觉得很make sense。合作社其实也不那么去中心化,因为合作社从小到大有很多,在台湾七个人就可以搞合作社。我在台湾搞了一个合作社,一开始就七个人,我们是有政府颁发的执照的正式艺术家合作社,是全世界第一个。七个人中每个人既是Shareholder也是Stakeholder。所以我觉得这个基础其实是很重要的。

South Korea has Asia’s most progressive cooperatives, as it only needs three people to form one. They have countless mom-and-child or daycare cooperatives subsidized by the government. A full-time mom might say, “Help me care for my kids so I can work,” starting with three mothers and growing to hundreds, rotating childcare duties. This organic growth, started when the kids are very young, makes perfect sense for me. Cooperatives aren’t inherently decentralized, and they can be large or small—Taiwan allows seven people to form one. I co-founded the world’s first licensed artist cooperative with seven members in Taiwan, each of them is both shareholder and stakeholder. This foundation matters.

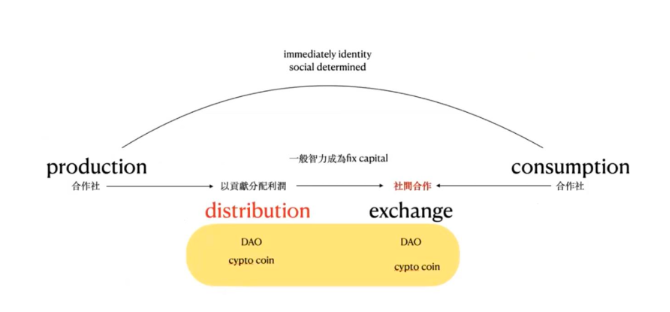

935: 您之前在文章里提到一个观点,在马克思分析整个生产与消费过程整个四个步骤:生产(Production),分配(Distribution),交换(Exchange)和消费(Consumption)当中,你是觉得现在Web3只解决了中间的交换步骤里的问题,但是没有改变两端的生产和消费。

935: In your earlier writings, you noted that within Marx’s four stages of production/consumption—production, distribution, exchange, and consumption. You said that Web3 only addresses issues in exchange, not in production or consumption.

Michel Bauwens也提到,过去我们在地的生产模式,用他的话说叫共享资源(Commons),这种生产模式是资源保护型的,它是滋养型的。它不像资本主义那样把一个地方的资源经济意义最大化并且消耗掉。滋养型的生产,其实更符合长期的整体利益。他也提到像合作社本身,正是因为他比较小,他可以有更多的在地性的关注。但是这这种小型的Commons又可能只局限在一小片的区域,某一种单一的文化里面。所以在面对跨国的、大型的,或者说是非常强大的集权,现代化政府的时候,它很容易被吞噬掉,被异化。所以Michel的一个思路是,结合刚刚说的Scalability,他觉得我需要要建立一个Global Commons。

Michel Bauwens also argues that localized production models, or "commons," are resource-nurturing, unlike capitalism’s extractive approach. Small cooperatives can focus on local needs but risk being swallowed by transnational powers or centralized governments. His solution is a "Global Commons" combined with scalability.

黄孙权: 对,我认为Web3没有办法解决生产(Production)和消费(Consumption)的问题。很多人都在想做这件事(Global Commons),就像比特币一开始要让全世界人都可以点对点交易一样。但是最终的目的地离你很远,你用这种目的地不见得可以号召什么事情,因为能够被号召的人其实都是对这种技术跟这种Scalability有一点想象的。最在地的(Local),更需要帮助的人根本不会想这事儿。我今天日子都过不了了,你明天要告诉我,跟全球人连结,这不好笑么?因为我是搞运动出身的,所以我不会那么乐观。这其实是你们下一代要做的事,我只是在旁边唠叨你们。

Huang Sunquan: Right. Web3 can’t solve issues in production or consumption. Many aim to build global commons, like Bitcoin’s original vision of a peer-to-peer global transaction tool. But distant ideals struggle to mobilize grassroots communities. If you’re struggling to survive today, why care about global connectivity? As an activist, I’m pragmatic and pessimistic—but this is your generation’s task, I’m just a person rabbiting on aside.

欧洲发行的Faircoin就是做的这个事情,它想把所有的平台和社区容纳进来,用Faircoin做通货。但是不成功,原因就是因为太难对价了。比如说一个生产稻米的生产合作社,和一个劳动合作社,以及一个开摩的的公共运输工会,这三个社区要怎么对价的?最后还是要兑换成法币。在地的事情(Locality)基本上就是跟国家(Nation State)更有关联。但哪一个加密货币不是跟主权国家玩呢?现在整个加密货币在幻想自己不受主权国家的控制,但根本没有嘛,在每一个国家里都受控制。

Europe’s Faircoin tried to unite platforms and communities under one currency but failed due to valuation hurdles. Let’s say, how would a rice cooperative, a labor cooperative, and a motorcycle taxi union exchange value? They’d eventually default to fiat. Locality ties more closely to nation-states—even cryptocurrencies, while imagining themselves free from nation control, play by sovereign rules in every country.

我觉得最最可惜的事情是,这些东西都没有脱离资本主义对货币的想象。比如说比特币一开始是金本位,就是一个老套的货币系统。POS就是股票制。这些技术其实做的都是非常旧的事情,包含所有旧有的意识形态在里头。所有的价值体系并没有被改变,只是流通(Circulation)的技术变了而已。那我们为什么要这样干?资本主义的核心概念是Circulation,因为它不流动就死掉了。加密货币也是一样,所以这两个东西对我来说没什么两样。但问题是在流动过程中怎么Build community和Commons,这才是关键。为什么这么多人在讨论community,但我根本看不到你们的Community到底长什么样子。

The real tragedy is that nothing escapes the monetary image of capitalism. Bitcoin mimics gold standards; Proof-of-Stake replicates stock systems. These are old ideologies repackaged. Value systems remain unchanged—only circulation tech evolves. Capitalism and crypto both depend on circulation, so they are similar for me. The key is building communities and commons within circulation. Why talk endlessly about "community" without showing me a real one?

我们也曾经邀请Michel来台湾,他其实很可爱。也不能说他不对,但感觉他的想法里有很多欧洲人搞Commons的想象。其实我们自己整个东南亚社群,我们有非常强的不同于北方中心的东西。比如说,大陆很多的原住民社群,像是侗族,还是有那种很强的Commune*的感觉,它就是一个生活集体。台湾的众多原住民也有。我们有很多东西,但我们从未看过他们。我们一直在看别处的社会,这是奇怪的。

We once invited Michel Bauwens to Taiwan—he’s earnest, but his Commons vision feels Eurocentric. Southeast Asian communities, like China’s Dong ethnic group or Taiwan’s indigenous tribes, have lived in communal systems for centuries. Yet we ignore these local models while chasing foreign ones.

我可以讲另一个从原住民身上学到的东西。我们有一个叫邵族,他们在日据时期被屠杀过,现在全台湾只有一百多个人是纯邵族,其他都是混血。他们过年有大年跟小年,小年三天,大年七天。七天里每家每户都开门,一直喝酒喝到死,他们有七大家族,每一年都要开会,决定要办小年还是大年。有一次开会允许我朋友去旁观,七个族长在那边开始喝酒,一直笑。我朋友想他们什么时候开始讨论,因为根本没有讨论。也不讨论,也不投票,怎么决定?然后突然有个人说:“我们今年,小年吧。“然后说所有人都说好,那就小年。

Let me share a lesson from Taiwan’s Thao people. Nearly wiped out during Japanese rule, only 100 pure-blooded Thao remain. During their New Year, seven clan leaders gather to decide whether to celebrate a "major" (7-day) or "minor" (3-day) festival. Once, my friend observed their meeting: the leaders drank, laughed, and never formally discussed or voted. As my friend was wondering how they were going to decide, suddenly, one leader said, “This year, minor?” and all agreed.

你知道为什么没有投票么?因为这七个族长完全知道这个村里头每家每户发生了什么事,经济状况好不好,他们有非常好的信任感,所以觉得今年大家都不是太丰盛,办大年大家会会花太多钱。所以一个人说小年,然后每个人都笑一笑,喝酒,小年吧,然后就结束。我朋友整个就看呆了。我一个这么相信民主跟投票的人,我觉得这种才是......我不能说它很棒,但有一种非常自然的:因为我们的信任在那儿,以至于我们可以做这个事情而不觉得有任何不对。

Why no vote? Because their trust and intimate knowledge of each household’s circumstances—This year hasn’t been particularly prosperous, and holding a major festival would cost too much. So everyone smiled and drank, decided to do a minor festival, and ended the meeting, leaving my friend stunned. As a democracy advocate, I don’t think this is perfect, yet this natural consensus, rooted in trust, made formal processes unnecessary.

*注:Commune在英文中普遍指社区式的生活,不局限于中文中的公社。

网研所的研究历史变迁和自己的目标:合作社与UBI

The Evolution of the Institute of Network Society’s Research and Its Goals: Cooperatives and UBI

7k:您近10年的研究,似乎可以在每年网络社会研究所年会的主题中看出一条脉络,在网络、合作社、空间和文化这几个关键词之间来回变迁。

7k: Your research over the past decade seems to follow a trajectory reflected in the themes of Network Society Annual Conferences, shifting between keywords like networks, cooperatives, space, and culture.

黄孙权:是的。我们一开始做年会,是因为我觉得中国拥有世界上最多的网民,但我们没有比较好的理论化自己的能力,所以前三届,是把那些非常尖锐的,网络社会该有的东西都讨论到了,从最哲学的(概念),到(最实际的)能源、物流等等。每一届选择的主题都是非常Local的,在中国当时发生的一些事,一直到第五届年会。疫情之前我们开始搞Crypto,这就进入了第六、第七届比较混乱的时候:我们开始考虑有crypto到底和我们之前关心的合作社有什么差别。第八届因为我们开始做旧金山和深圳(的纪录片),所以就开始谈反文化。

Huang Sunquan: Yes. Initially, we organized the conferences because I felt China, with the world’s largest internet user base, lacked robust theoretical frameworks to articulate its own experiences. For the first three conferences, we tackled the most urgent issues of network society—from philosophical concepts to practical matters like energy and logistics. Each theme was deeply local, rooted in China’s contemporary realities, up until the fifth conference. Before the pandemic, we began exploring crypto, leading to the more chaotic sixth and seventh conferences, where we questioned how crypto differed from our earlier focus on cooperatives. The eighth conference shifted to counterculture as we started documenting San Francisco and Shenzhen.

其实简单讲,在我短期有限的能力范围里,我一直只有两个目标,其中一个是做合作社,不管是数字的还是其他形式的合作社都可以。另外一个就是UBI。UBI有很多种弹性,Coop其实基本上就是一个UBI系统,而UBI是一个把我所有享受的利益给社会外部化的过程。这两个是我最想做的。

To put it simply, within my limited capacity, I’ve always had two goals: advancing cooperatives—digital or otherwise—and promoting Universal Basic Income (UBI). UBI is flexible, and Coop essentially functions as a UBI system, externalizing shared benefits into society. These are my primary focuses.

所以我们年会是一直都在处理这个事情。第一个是我们要面对在中国和在东南亚非常真实的社会条件,第二个是我还是希望把这个事情推到一个比较可见的实践范围内,让我们知道我们下一步可以干嘛。

Our conferences have consistently addressed these aims. First, we confront the real social conditions in China and Southeast Asia. Second, I hope to push these ideas into visible, actionable realms, clarifying our next steps.

Review/Kurt Pan

这篇访谈勾勒了从冷战时期至今,互联网文化和加密技术如何在历史大潮、社会运动与意识形态的纠缠中演进。访谈对"技术缺乏自有意识形态,却易被自由意志论渗透"的观点具体而深刻,指出了加密运动固有的张力:一方面,它承载了反建制、强调个人自由与隐私的愿景;另一方面,却又往往落入加州式全球化及资本累积的逻辑,忽略了在地需求与真实的底层群体。

在对加密技术的批判与期许方面,受访者多次强调"社会运动的力量先于技术的应用"。从历史上美国黑客运动能与公民运动结合,到台湾社会运动成功撼动公共政策,再到原住民族群与合作社的实践经验,受访者都展示了"只有立足在地需求与公共利益的技术,才真正会带来进步"。这与不少 DAO 与 Web3 项目在实践中遇到的困境形成对照:若只强调技术机制(例如治理投票、代币激励),却缺乏真正扎根社群的互信、协作与公共讨论,那么"去中心化"往往流于形式。访谈并不否定加密技术的潜力,而是指出了它更深层的前提:在地社会文化力量、合作组织以及扎实的社群互动,才可能把新工具用来推动有意义的改变。对那些希望以加密技术抵抗巨型平台垄断或市场极端化的人来说,访谈提供了重要的反思:究竟应该如何重新定位"自由"与"社群"的意义?如何在落实民主、降低不平等的同时,保持技术的开放创新?这些问题都需要更多从地方经验、社会运动实践层面出发的回应,而不只是依赖技术自身的"去中心化"想象。

整体而言,本文最具启发之处在于把"技术哲学与社会运动"紧密相连。它既提醒我们反思互联网与加密文化背后的历史与意识形态,也启迪了更深层的想象:若缺乏真实的公共意义与地方价值,任何技术都不会自动带来进步;而当技术能与社群互惠、与社会运动相结合,才有机会催化真正有意义的社会变革。此外,在一个文明娱乐至死近乎疯癫,民众分离分裂攻讦谩骂,暴力机器和自我对人类理性和良知双重审查严格限制的时代,这篇访谈依然在坚守着一件在过去世代稀松平常但现在比黄金还珍贵,以至于很多Gen Z乃至Gen Alpha闻所未闻的事情:"发自内心真诚地进行有效的批评"。仅此一点,我就愿对本文给出满分的评价。

This interview outlines how internet culture and crypto technology have evolved from the Cold War era to the present—entwined in the grand currents of history, social movements, and ideological struggles. It offers a concrete and profound perspective on the notion that “technology lacks an inherent ideology yet is easily permeated by libertarian ideas,” highlighting the inherent tensions within the crypto movement: on one hand, it carries a vision of anti-establishment values that emphasize individual freedom and privacy; on the other, it often falls into a California-style logic of globalization and capital accumulation, overlooking local needs and the realities of grassroots communities.

Regarding the critique and expectations of crypto technology, the interviewee repeatedly stressed that “the power of social movements comes before the application of technology.” From the historical fusion of American hacker movements with civic activism, to the successful impact of Taiwanese social movements on public policy, and even to the practical experiences of indigenous communities and cooperatives, the interviewee demonstrated that only technology anchored in local needs and public interest can truly foster progress. This stands in stark contrast to the difficulties encountered by many DAO and Web3 projects in practice: if the focus is solely on technical mechanisms (such as governance voting and token incentives) without genuine community trust, collaboration, and public discourse, then “decentralization” often becomes merely a formality. The interview does not deny the potential of crypto technology; rather, it points out a deeper prerequisite—that only through local socio-cultural forces, cooperative organizations, and robust community interactions can new tools be harnessed to drive meaningful change. For those hoping to use crypto technology to resist the monopolies of giant platforms or extreme market forces, the interview provides important food for thought: How should we redefine the meanings of “freedom” and “community”? How can we maintain technological open innovation while implementing democracy and reducing inequality? These questions demand responses grounded in local experiences and the practices of social movements, not merely the abstract ideal of “decentralization” inherent in technology.

Overall, the most inspiring aspect of this article is its close interweaving of “technology philosophy and social movements.” It reminds us to reflect on the history and ideology behind internet and crypto cultures while inspiring a deeper vision: without genuine public significance and local value, no technology will automatically bring progress; only when technology works in mutual benefit with communities and aligns with social movements can it catalyze truly meaningful societal change. Moreover, in an era when our civilization is nearly driven mad by endless entertainment, marked by public fragmentation, divisiveness, and rampant personal attacks—with violent mechanisms and self-imposed censorship severely restricting human reason and conscience—this interview steadfastly upholds something that was once commonplace in previous generations yet is now more precious than gold (so much so that many in Gen Z and even Gen Alpha have never heard of it): “to engage in sincere and effective criticism from the heart.” For that alone, I would award this article a full score.

✨ Tip

受文章篇幅所限,对黄孙权老师的访谈被拆为上下两部分。本文系下篇,上篇地址:

Limited by the length of the article, the interview with Mr. Huang Sunquan was divided into two parts. This article is the B-side.

A- Side:

Uncommons

Reporter: 935&7k

Review: Kurt

Edit: 0614

👇Re

《南塘合作社的民主方法论》 三联生活周刊 https://www.lifeweek.com.cn/article/26247

Coop白皮书https://github.com/CAAINS/COOP/blob/main/Chinese_whitepaper.md

文化与技术三部曲|个人计算机与反文化篇:互联网档案馆创始人Brewster Kahle访谈影片

https://caa-ins.org/archives/12046

个人计算机与反文化篇(二):专訪斯坦福传播学教授 Fred Turner

https://caa-ins.org/archives/12353

个人计算机与反文化篇(三):专访纽约时报记者与作家John Markoff

https://caa-ins.org/archives/12528

Who we are 👇

Uncommons

区块链世界内一隅公共空间,一群公共物品建设者,在此碰撞加密人文思想。其前身为 GreenPill 中文社区。

Twitter: x.com/Un__commons

Newsletter: blog.uncommons.cc/

Join us: t.me/theuncommons

Discussion